|

|||||

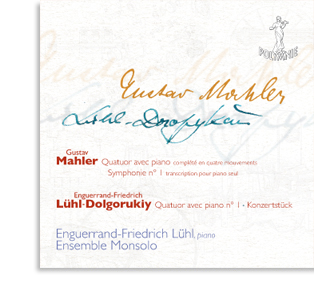

Mahler •

Quatuor avec piano, Symphonie n° 1

Lühl • Quatuor avec piano n ° 1 ,

Konzertstück

Enguerrand-Friedrich Lühl-Dolgorukiy, piano • Ensemble

Monsolo : Samika Honda, Sylvain Favre, violons

; Sylvain Durantel, alto ; Sébastien van Kuijk, violoncelle

POL 550 283

Commander

sur Clic Musique !

Mahler

Quatuor avec piano

complété en quatre mouvements par Lühl-Dolgorukiy

Nicht zu schnell

Scherzo

Langsam und empfunder

Finale

Lühl-Dolgorukiy

Quatuor avec piano n° 1 LWV 121

Allegro assai

Allegro con spirito

Lento amoroso

Allegro risoluto

Lühl-Dolgorukiy

Konzertstück LWV 19

Presto possibile

Mahler

Symphonie n° 1

transcription pour piano seul

Des jours de la jeunesse

Printemps sans fin

Blumine • Andante

Toutes voiles dehors • Scherzo

La Comédie humaine

Echoué sur le sable De l’Enfer

* premiers enregistrements mondiaux

GUSTAV MAHLER • QUATUOR AVEC PIANO

La première transcription que fit Lühl, à 14 ans, fut celle de la Première Symphonie de Gustav Mahler (LWV 1 dans son catalogue). Il mit six mois, et ce travail l'éveilla aux sciences de l’orchestration et de l’écriture. Grand admirateur de Mahler, il ne cessa par la suite d’entreprendre la transcription d’autres œuvres du maître autrichien, notamment la Cinquième Symphonie.

Premier mouvement du quatuor original de Mahler

Mahler entra au Conservatoire de Vienne en 1875. À cette époque

il avait déjà composé plusieurs lieder et pièces de musique de

chambre. Citons Henry-Louis de La Grange dans son ouvrage

monumental :

« Sans doute, durant sa seconde année au Conservatoire, Mahler

partage-t-il pendant deux mois une chambre avec [Hugo] Wolf et

Krzyzanowski. Tous trois vivent alors en bonne intelligence et se

jouent mutuellement leurs œuvres récentes. Wolf semble même avoir

alors considéré ses lieder inférieurs à ceux de ses deux amis. En

une nuit, Mahler compose là au piano, un mouvement de quatuor pour

un concours du Conservatoire, tandis que les deux autres sont

contraints d’aller dormir dehors sur les bancs du Ring . […]

Mahler compose néanmoins sans cesse, pour le Conservatoire et

aussi pour lui-même. Seuls de courts fragments ont subsisté de

cette époque : un mouvement de Quatuor avec piano de 1876, un

début de Scherzo pour la même combinaison et deux fragments de

Lieder. […] La page de titre de ce mouvement de quatuor porte :

Clavier Quartett ; Erster Satz : Gustav Mahler ; 1876. Au-dessous

du titre figure l’estampille de l’éditeur de musique Theodor

Rättig, ce qui semble indiquer que Mahler lui avait soumis

l’ouvrage en 1878, année où Rättig publie l’arrangement à quatre

mains de la Troisième Symphonie de Bruckner. Comme pour beaucoup

d’autres manuscrits de jeunesse, Mahler a laissé courir sa plume

dans les marges et sur la page de titre ; de même que celles des

esquisses de Das Klagende Lied, elles sont couvertes de

griffonnages et d’arabesques complexes. »

Le premier mouvement et le Scherzo inachevé ont été publiés en

1973 par Peter Ruzicka, aux éditions Sikorski de Hambourg

[partition sur laquelle s'est appuyé Lühl pour ses recherches].

Le fait que le premier mouvement et les esquisses du Scherzo aient

figuré dans le même classeur semble indiquer qu’il s’agissait de

deux parties du même ouvrage. Pourtant, il paraît inhabituel, pour

un élève de Conservatoire, de composer un Scherzo en sol mineur

pour une œuvre en la mineur. Dans le premier mouvement, la graphie

est nette. Seules les trois dernières pages trahissent la hâte du

compositeur. Pour les dernières mesures, la main gauche du

pianiste exécute un long trémolo sur la tonique, au-dessus duquel

le jeune homme a griffonné à la hâte le mot Orgelpunkt (point

d’orgue).

Les modèles évidents du musicien, pour cet exercice d’école sont

Schumann et Brahms, ce qui n’a rien de bien surprenant puisque

Julius Epstein, son maître au Conservatoire, a été l’un des

premiers interprètes de la musique de piano et de chambre de

Brahms et que Franz Krenn et Robert Fuchs, professeurs de

composition et d’écriture, sont bien connus pour leur fidélité à

la tradition.

Le Scherzo inachevé

Toutes les pièces de jeunesse de Mahler, lieder ou musique de chambre, ont été perdues ou détruites. Il ne reste que quelques fragments d’œuvres, soigneusement conservés par les archivistes des bibliothèques Mahler à Paris et à Vienne.

En 1991, le jeune Lühl décida de compléter le Scherzo inachevé.

Schnittke l'avait déjà fait, dans son propre style. Lühl décida,

lui, d’entreprendre un travail musicologique afin de cerner

l'écriture du jeune Gustav. Il reprit les esquisses publiées aux

éditions Sikorski (caractères d'imprimerie et fac-simile). “Le

texte manuscrit était pratiquement illisible. Mahler, écrivant

très vite et pour lui en tant qu’interprète de ses propres œuvres,

avait l’habitude d’insérer dans ses phrases des raccourcis de tout

genre - évidents à ses yeux - pour éviter d'inutiles répétitions.

Il lui arrivait parfois d’écrire la voix principale à un

instrument pour lequel elle n’était pas destinée. Des notes qui ne

sont pas alignées, des accords à peine complets, des mesures vides

car contenant d'évidentes formules d’accompagnement, tout cela

était monnaie courante dans l’écriture du jeune compositeur. Ce

qui rend d'autant plus difficile le travail de l’éditeur.” Lühl

consulta à la bibliothèque Gustav Mahler de Paris une reproduction

du manuscrit (l'original étant à l’époque conservé à la Pieront

Morgan Library de New York). La première page originale fut

maintenue dans son intégralité, même si les modulations

improbables de la fin - révélatrices de l'art de composer de

Mahler - rendirent difficile l’enchaînement de certains passages.

La formule de doubles croches du piano était, quant à elle, à

l’origine écrite à l’alto, mais très difficile à jouer et ne

sonnant pas bien.

Le retour du thème principal est dans l’esprit de Mahler, même si

celui-ci l’avait noté, après des mesures de blanc, en la mineur.

Lühl reprend, après la progression chromatique et la cadence, le

développement de la première période, rappelant les enchaînements

harmoniques du premier mouvement. Le piano reste l’instrument

d’accompagnement et les cordes se répondent en imitations

resserrées.

Une citation du premier mouvement et un bref clin d’œil au thème

choral de la fin du deuxième mouvement de la Cinquième Symphonie

font culminer cette première partie dans une apothéose de courte

durée. Le ‘Halt’ – arrêt – fait référence aux tics de langage de

Mahler dans ses partitions orchestrales. Une transition de trois

mesures, une sorte d’écho aux différents instruments, rappelle les

sons des cors dans la préparation au Trio du Scherzo de la

Première Symphonie.

Le Trio, la partie centrale, est exclusivement emprunté au Lied n°

4 des Kindertotenlieder, ce dernier lui aussi composé dans la même

tonalité (mi b majeur). L’effet ondulant des formules

d’accompagnement du piano rappelle la prédilection de Mahler pour

les musiques de foires et de fanfares. Des modulations abruptes

dans les tons homonymes sont typiques chez Mahler et fréquemment

utilisées dans son œuvre (ici mi b Maj/min après une cadence). Une

petite cadence expressive au violon est également tirée du Lied n°

4 des Kindertotenlieder. Une courte transition ramène à la

première période (Scherzo) écourtée. Comme dans le premier

mouvement, la fin se décline sur trois accords de pizzicato.

Ces deux premiers mouvements du Quatuor de Mahler/Lühl furent

créés au CNSM de Paris le 7 Mars 1994, sur une initiative du

violoniste Jean Moullière, professeur de musique de chambre. Ils

furent redonnés, toujours grâce à Jean Mouillère, deux ans plus

tard à la Sorbonne, à l'occasion de la conférence sur Mahler de

l'historien et musicologue Serge Gut.

Malgré cela, il fut difficile pour Lühl de faire reconnaître son

travail. L'œuvre fut remise à la Société Mahler à Vienne, au

pianiste Manfred Wagner, à la Internationale

Gustav-Mahler-Gesellschaft de Vienne... sans succès. Les

bibliothèques de Paris et de Vienne se disputaient sur la

provenance du fragment original, et un travail de reconstruction

d’après des esquisses était tout bonnement impensable. Qu'à cela

ne tienne, Lühl termina l'œuvre avec deux autres mouvements, en

une nuit, à la lumière des bougies.

Le troisième mouvement, le mouvement lent, tire son origine du

livre de Henry-Louis de La Grange sur Mahler (tome III), d'un

appendice à la fin de l’ouvrage où l’auteur mentionne l’existence

identifiée et archivée de fragments d’œuvres inachevées ou perdues

: “Le 15 et le 16 mars 1981, l’Orchestre RIAS de Berlin-Ouest a

donné, sous la direction de Lawrence Foster, la première audition

d’un ‘Prélude Symphonique de Gustav Mahler’, orchestré par le

musicologue hambourgeois Albrecht Gürschnig5. Renseignements pris

auprès de ce dernier, il s’agissait de l’orchestration d’un

manuscrit appartenant à la Nationalbibliothek de Vienne et dont la

page-titre porte la mention suivante : “Prélude Symphonique,

d’après la copie d’un élève de Bruckner, Rudolf Krzyzanowski, de

l’année 1876, censément d’Anton Bruckner. Transcription pour piano

d’après la partition [d’orchestre] de Heinrich Tschuppik.” Au bas

de la page a été ajoutée la note suivante : “Pourrait-il s’agir

d’un travail de Gustav Mahler, réalisé pour un examen ?

Krzyzanowski a collaboré avec Mahler à la transcription pour piano

à 4 mains de la Troisième Symphonie de Bruckner (deuxième

version)”. On perd alors la trace de la partition que Tschuppik a

transcrite. Son manuscrit comprend huit feuillets à 16 portées,

dont une double-page servant de couverture, et trois pages

blanches. Certains passages sont notés sur trois portées, avec

quelques indications concernant l’orchestration originale.

L’ensemble est composé de 292 mesures et le tempo indiqué est

nicht zu rasch [pas trop vif]. Le morceau commence par le thème

suivant des basses, accompagné par un ostinato typiquement

brucknérien.”

Le thème en progression permanente au violoncelle débute, comme

souvent chez Mahler, par une quarte, et est truffé d’appoggiatures

ultra-expressives. Dans la deuxième partie plus enjouée en mineur,

Lühl a pensé au mouvement lent de la Première Symphonie (sur

‘frère Jacques’). L’immense progression évoque le travail soigné

de Mahler pour les traitements en imitation. La désinence amène

une période de flottement, également inspirée du même mouvement

symphonique, avant de retourner à la réexposition, écourtée et

enrichie d’un point culminant juste avant la fin (mi Majeur).

Le Final

Les mouvements 3 et 4 s’enchaînent et sont reliés par une brève

introduction au final. De La Grange remonte aux sources : “À la

mort d’Alma (l’épouse de Mahler), deux esquisses manuscrites et

n’appartenant à aucune œuvre connue de Mahler étaient comprises

dans sa collection. Elles se trouvent aujourd’hui, l’une à la

Pierpont Morgan Library de New York et l’autre à la

Stadtbibliothek de Vienne. Elles ont toutes deux été examinées

dans les années 1920 par Alban Berg qui a rédigé à leur sujet une

page manuscrite confirmant qu’elles n’appartenaient à aucune œuvre

connue. Selon lui, les chiffres au crayon bleu semblaient avoir

été écrits à la fin de la vie de Mahler, qui paraissait donc avoir

eu l’intention de se resservir de ces esquisses à une date

ultérieure. D’après Susan Filler, qui a étudié de près l’écriture,

ainsi que le papier utilisé, les deux esquisses dateraient en fait

des environs de 1900, et il s’agit de Particelle, chacune

comprenant de nombreuses variantes de certains passages. La

première esquisse, pour un Presto en Sol majeur (Mahler exprime

dans une note l’intention de transposer le tout en Fa) comprend

trois feuillets.”

Cependant, pour garder une unité tonale du quatuor, Lühl décida de

transposer le thème en la Majeur pour terminer le cycle de quatre

mouvements dans une atmosphère allègre et vive, conforme à l’air

du temps. Chacun sait que les compositeurs se citent, se recitent

et se plagient parfois avec allégresse et sans scrupules : Mahler

n’a pas hésité à faire usage de ce processus en notant les

prémices de ce qui allait devenir le thème de fanfare d’ouverture

de la Cinquième Symphonie dans le premier mouvement de sa

Quatrième. Ce thème du rondo a été remanié de manière à garder la

fraîcheur juvénile d’un Mahler âgé de 16 ans. Les périodes de

couplets sont teintées de son cycle de Lieder Des Knaben

Wunderhorn, dont il n’a cessé d’utiliser les thèmes dans ces

quatre premières symphonies, notamment pour le présent exemple les

Troisième et Quatrième Symphonies. Dans le deuxième couplet, Lühl

tire la formule d’accompagnement d’arpèges au piano et les

enchaînements harmoniques du premier mouvement, sans toutefois en

faire une citation directe. La dernière progression vers la fin

rappelle fortement la fin du Scherzo de la Première Symphonie et

une succession d’accords scandés en la Majeur rappelle

l’académisme avec lequel Mahler devait suivre sa formation au

Conservatoire. Lühl voyait ici un message à faire apparaître à

travers l’œuvre : ce quatuor devait contenir les germes du

Klagende Lied et de la Première Symphonie, qui suivirent quelque

temps après.

Le quatrième mouvement fut créé Salle Pleyel le 4 avril 1998, puis

l'œuvre entière à Lille en avril 2004.

Note de l’auteur à propos de la création du Quatuor Mahler/Lühl (traduit de l’allemand)

“C’est le souhait de chacun de savoir ce qu’un compositeur aurait

pu créer si la mort ne l’avait pas retenu. Des œuvres inachevées

sont de grandes frustrations intellectuelles pour l’auditeur ou le

musicologue ; d’un autre côté, elles ouvrent une voie étroite qui

mène au monde infini de l’hypothèse. On voudrait en savoir plus et

on espère trouver une explication, comment le compositeur aurait

pu terminer sa pièce… sans jamais pouvoir en recevoir une réponse.

Afin d’atténuer cette frustration, il arrive dans l’histoire de la

musique que des élèves, des amis ou de fervents admirateurs du

défunt artiste, acceptent le délicat défi de compléter des

esquisses et ébauches, en espérant suggérer par ce travail que le

compositeur vit toujours parmi nous. Ainsi naquirent la Septième

Symphonie de Tchaïkovski (S. Bogatryriev), le troisième concerto

de Chopin (J-L. Nicodé), l’opéra de Weber les Trois Pintos (Mahler

lui-même), la Dixième Symphonie de Mahler (D. Cooke)… et ce

présent quatuor avec piano.

La date de création du premier mouvement (1876) a longtemps été

remise en cause, mais elle a été soutenue par une tradition et

s’est fixée sur cette date au fil des années. La façon d’écrire

rudimentaire et parfois illisible de Mahler au jeune âge nous

indique que Mahler écrivait dans le seul but de représenter

lui-même ses propres œuvres. Lorsque je me mis à écouter plusieurs

interprétations de ce mouvement ‘relique’, je remarquai en

comparant toutes les versions qu’elles différaient non seulement

par l’interprétation, mais plus techniquement par certains détails

d’écriture. Les interprètes se crurent obligés de corriger telle

ou telle note [dans le cas de l’interprète non compositeur, il ne

pouvait que se limiter à une correction minime – note de l’auteur

aujourd’hui] pour plus de logique dans le sens des phrases

musicales. Donc je décidai, alors âgé de 16 ans, comme Mahler à

son époque, de mettre ma connaissance musicale de compositeur à

l’épreuve et commençai à ‘nettoyer’ la partition de manière plus

approfondie.

Mais cela ne me suffisait pas et je découvris les pages à 24

systèmes d’un deuxième mouvement, d’un Scherzo ! J’acceptai

également ce nouveau défi, mais je disposai de bien moins de

matériel que dans le premier mouvement et de nombreuses mesures

étaient illisibles ou incompréhensibles harmoniquement.

C’est ainsi que je pus jouir pendant quelques jours du privilège

exceptionnel de travailler avec Mahler et je me jetai avec un

énorme engagement dans ce projet du jeune et prometteur

compositeur autrichien. Après quelques représentations je sentis

que quelque chose manquait à l’ensemble. Je voulais entendre plus,

je voulais faire des deux mouvements un quatuor complet, un

‘quatuor de Gustav Mahler’, qui sonnerait ‘comme du Mahler’

jusqu’à la dernière note. C’est ainsi que naquirent d’un trait et

en une nuit le troisième mouvement et le final et j’espère avoir

été à la hauteur de cette tâche – l’agrandissement et

élargissement de la plus jeune source créative de son évolution

musicale – en hommage à un homme que j’admire et respecte

énormément.

Enguerrand-Friedrich Lühl, Paris, printemps 1999

ENGUERRAND-FRIEDRICH LÜHL • QUATUOR AVEC PIANO LWV 121

Composé en quelques jours en 2008, le Quatuor avec piano LWV 121

précède de peu le Quatuor à cordes n° 5. Lühl a eu l’idée d’une

nouvelle forme musicale. Le deuxième mouvement est inséré au

troisième ; jusque là rien d’exceptionnel, si ce n’est qu’en fait,

d’un point de vue structurel, les deux mouvements ne font qu’un et

que le mouvement lent n’est en réalité que la partie centrale du

scherzo. Les deux mouvements créent une longue fresque et les deux

thèmes, d’apparence radicalement opposée de par leur vitesse et

atmosphère, sont en fait étroitement liés par leur construction.

Le final, en forme de rondo, reprend dans ses couplets les rappels

des autres mouvements dans l’ordre chronologique. L’impression

donnée à l’écoute de ce quatuor est celle d’un voyage sans

escales, malgré les quelques interruptions (ou ‘fausses’

interruptions !) entre et pendant les mouvements.

KONZERTSTÜCK LWV 19

Cette pièce folle et brillante est un arrangement d’une étude

pour piano (LWV 15 – printemps 1994). Son style rappelle celui

d’un ‘bis’ de concert, idéal pour terminer une soirée de musique

foncièrement romantique. Son auteur a également arrangé cette

étude pour deux pianos (Konzertetüde LWV 145), un arrangement non

moins virtuose et éclatant.

CD 2

GUSTAV MAHLER

SYMPHONIE n° 1 “Titan” pour piano seul

En 1889, la presse austro-hongroise eut un regard dévastateur

face à la Première Symphonie de Gustav Mahler, jeune compositeur

morave, certes prometteur, mais peut-être trop audacieux pour les

oreilles et attentes de ces messieurs les critiques. L’œuvre fut à

l’origine du style proprement mahlérien, une sorte d’introduction

aux autres symphonies qui allaient suivre. Les harcèlements des

critiques ne firent en rien reculer le compositeur dans sa

recherche esthétique.

Achevée en 1888 et créée dans sa première version à Budapest le 20

novembre 1889, la Première Symphonie connaîtra cinq versions dont

quatre musicalement déterminantes. De nombreuses annotations

figurent également sur les bons à tirer de son éditeur Universal

Edition à Vienne en 1906. Dans son cycle de jeunesse, les Lieder

eines fahrenden Gesellen, antérieurs à Titan (1883-85), figure

l’essentiel du matériau thématique que Mahler utilisera jusqu’à sa

Quatrième Symphonie. Le second mouvement se réfère à un lied

encore antérieur au Fahrender Geselle, Hans und Gretel. Mahler,

sous le choc de l’échec de Budapest, inclut dans le programme d’un

concert à Hambourg en 1993, une explication narrative de la

symphonie. L’œuvre comporte cinq mouvements, une division centrale

en deux parties marque une pause. Elle s’intitule Poème musical en

forme de symphonie.

Première partie : “Des jours de la jeunesse”

I. Printemps sans fin ; la partition porte l’indication “des

bruits de la nature”

II. Blumine - Andante

III. Toutes voiles dehors - Scherzo

Deuxième partie : La Comédie humaine

IV. Echoué sur le sable – marche funèbre à la manière de Callot

V. De l’Enfer (à Weimar, pour la représentation de 1904, le titre

fut complété par De l’Enfer au Paradis

Blumine fut supprimé de l’œuvre, perdu puis retrouvé, et

s’inspire d’une source littéraire différente de celles citées par

Mahler dans les descriptions programmatiques des autres

mouvements. Le thème caractéristique à la trompette dès les

premières mesures est tiré d’un opéra inachevé : Der Trompeter von

Säkkingen, d’après l’œuvre littéraire de J.V. von Scheffel. Le but

de ce mouvement était d’illustrer les pensées ‘fleuries’ et

amoureuses du héros de la symphonie, encore nourri par l’élan

passionnel de la jeunesse.

Mahler parle de son œuvre comme suit : “Mes symphonies expriment

ma vie tout entière. J’y ai versé tout ce que j’ai vécu et

souffert, elles sont vérité et poésie devenues musique. Pour

quiconque sait bien écouter, ma vie entière s’éclaire”.

À l’âge de dix ans et demi, Lühl était déjà passionné par

l’héritage du maître viennois, alors qu’il venait de débuter le

piano avec sa mère, fine pédagogue et pianiste amateur. Le

professeur Michel Carcassonne, chirurgien en Chirurgie pédiatrique

à Marseille, avait montré en 1987/88 au tout jeune musicien sa

collection impressionnante de partitions. Bien que n’étant pas

musicien, il avait glané un répertoire précieux d’ouvrages en

partie épuisés ; parmi eux figuraient les neuf Symphonies de

Mahler pour piano à quatre mains. Lühl était fasciné par la

qualité du travail de réduction et il projeta la transcription

pour piano seul de l’intégrale des Symphonies de Mahler…

Finalement, le projet s’arrêta à la première.

Suite au projet d’enregistrement chez Polymnie de l’intégrale de

ses œuvres, Lühl a décidé de transcrire également Blumine, de

manière à présenter au public la version la plus complète de la

symphonie. Ce mouvement, transcrit en 2010 (inscrit dans son

catalogue avec le numéro… 172 !), fut rajouté à l’ensemble en

première audition dans cet enregistrement.

Enguerrand-Friedrich Lühl-Dolgorukiy, pianiste, compositeur, chef d'orchestre

Après avoir terminé brillamment ses études de piano à la Schola

Cantorum, Lühl complète sa formation en entrant à 15 ans au CNSM

de Paris. Trois ans après, il obtient un Premier Prix de piano à

l’unanimité. Parallèlement à son cursus de piano, il suit des

cours d’analyse musicale, de jazz, de musique de chambre, de

direction d’orchestre, d’harmonie et de contrepoint. Après ses

études, il entre dans le monde charismatique du Concours

International et s’y consacre pleinement. Dès 1998, il devient

lauréat de plusieurs Concours Internationaux, notamment Rome,

Pontoise et le Tournoi International de musique. Depuis, il

fréquente les grandes scènes d’Europe (récitals, musique de

chambre, avec orchestre). Il travaille depuis 2005 pour le

compositeur américain John Williams, pour lequel il transcrit les

partitions de ses plus grands thèmes de musique de films pour

piano seul et deux pianos. Il a enregistré en 2003 le CD John

Williams au piano vol. I avec ses propres arrangements des plus

grands thèmes d’Hollywood pour piano seul. Un deuxième volume

vient d’être enregistré avec les plus grands thèmes de Star Wars

pour deux pianos. Son catalogue de compositeur est conséquent :

six symphonies, deux concertos pour piano, de la musique de

chambre, diverses pièces pour soliste et orchestre, environ 120

pièces pour piano seul, des orchestrations et réductions, une

musique de film...

L’Ensemble Monsolo a débuté sa carrière en 2005, alors que ses

membres étaient encore étudiants au CNSM de Paris. Il a ainsi

bénéficié de l’enseignement de Jens McManama, Jean Mouillère,

Michel Strauss, Claire Désert, du Maggini Quartet et du Quatuor

Ysaÿe. Au sein du programme ProQuartet, Monsolo a également étudié

avec Walter Levin et Paul Katz.

L’Ensemble a depuis donné de nombreux concerts en France, Espagne,

Italie, Angleterre, États-Unis et au Japon, et a eu ainsi le

plaisir de partager l’affiche avec des musiciens tels que la

violoniste Marina Chiche, les violoncellistes Agnès Vesterman et

Alain Meunier, le saxophoniste Julien Petit, les pianistes Daria

Hovora, Dana Ciocarlie, Delphine Bardin, Kotaro Fukuma, et

François-Joël Thiollier. C’est en compagnie de ce dernier qu’il

eut le privilège d’enregistrer pour Polymnie le Quintette op. 70

de George Onslow (POL 550 162), récompensé par un 5 de Diapason.

Monsolo a également gravé les Concertos pour deux pianos de

Jean-Sébastien Bach, avec Hervé et Désiré N’Kaoua, ainsi que la

bande originale du film L’Empreinte de l’Ange de Safy Nebbou.

L’Ensemble Monsolo a reçu le Prix d’interprétation du Concours

international de musique de chambre d’Illzach en 2007, le Premier

Prix du Forum Musical de Normandie également en 2007, le Premier

Prix du Torneo Internazionale di Musica de Vérone en 2008, et a

été sélectionné par le programme Déclic de Cultures France et de

Radio France. C’est sur cette antenne qu’il s’est produit Dans la

Cour des Grands, de Gaëlle le Gallic, ainsi que dans le Cabaret

classique de Jean-François Zygel.

Aujourd’hui Monsolo, réunissant sur scène deux à dix musiciens,

offre à chacun de ces concerts une thématique originale propre à

rapprocher le public de la musique. Sa collaboration avec les

compositeurs actuels est un axe important de son activité. Déjà

dédicataire d’œuvres de Pierre Agut, Alain Weber, Maxime

Tortelier, et Dominique Preschez, il a créé en novembre 2009 le

Quintette à deux altos de Jacques Boisgallais.

![]()

Enguerrand-FriedrichLühl-Dolgorukiy, pianist, composer, conductor

Enguerrand-Friedrich Lühl-Dolgorukiy was born in Paris in 1975. He

started his studies as a pianist at the Schola Cantorum then

completed his training by entering the CNSM in Paris aged 15.

Three years later he obtained first Prize for piano. Parallel to

his piano cursus he studied music analysis, chamber music,

orchestral conducting, harmony and contrapoint. Since 1998 he has

won several international competitions and plays at prestigious

venues throughout Europe. The press is unanimous in considering

him as an international concert pianist. Since 2002 he has been

working with the production company Musique & Toile

specialized in the organisation of musical and film events for

which he plays his own arrangements for piano solo and duo of

Hollywood’s great film scores composed by John Williams. His 1300

pages of musical arrangements will be edited at a future date. He

also recorded a CD entitled “John Williams’ music vol. 1” A second

has just been recorded with more great themes from Star Wars for

two pianos. His composer’s catalogue is impressive: six

symphonies, two piano concertos, chamber music, various pieces for

soloist and orchestra, around 120 original pieces for piano,

orchestrations and arrangements, film music.

The Ensemble Monsolo began life in 2005 as a string quintet with

double bass, while its members were still studying at the Paris

Conservatory. Monsolo has had the opportunity to study under

eminent musicians such as Jens McManama, Jean Mouillère, Michel

Strauss, Alain Meunier, Claire Désert, the Maggini Quartet, and

recently has been receiving advice from the Ysäye Quartet, as well

as within the ProQuartet program with Walter Levin and Paul Katz.

The Ensemble Monsolo has performed naturally in France, but also

in Spain, Italy, England, the United Sates and in Japan, having

the great honour to play with renowned musicians such as Marina

Chiche (violonist), Alain Meunier, Agnès Vesterman (cellists),

Julien Petit (saxophonist), and Daria Hovora, Kotaro Fukuma,

Delphine Bardin, Dana Ciocarlie and François-Joël Thiollier

(pianists). It is with François-Joël Thiollier that Monsolo

recorded for the Polymnie label two Quintets by Georges Onslow,

with big pleasure. Monsolo has also collaborated in the recording

of Bach Concertos for two pianos with Hervé and Désiré N’Kaoua.

Monsolo also recorded the original soundtrack of Safy Nebbou’s

movie Mark of an Angel.

Monsolo received the interpretation prize at the International

Chamber Music Competition in Illzach 2007 (France), as well as the

First Prize at the Forum Musical de Normandie 2007 (France), and

the First Prize of the Torneo Internazionale di Musica 2008 in

Verona (Italy). Following these awards, Monsolo was selected for

the Declic programme of Cultures France and Radio France.

Monsolo’s performances for Radio France include the Cabaret

Classique with Jean-François Zygel, and Dans la Cour des grands

with Gaëlle le Gallic.Now, Monsolo has become an ensemble with a

varied combination of instruments, grouping from two to ten

musicians on stage. Collaboration with composers of the present

day is an important part of Monsolo’s activity. Composers such as

Pierre Agut, Alain Weber, Maxime Tortelier and Dominique Preschez

have dedicated their works to Monsolo, and in November 2009

Ensemble Monsolo will give the world premier of Jacques

Boisgallais’s Quintet for two violas.

CD 1

GUSTAV MAHLER • PIANO QUARTET

The first major work by Lühl regarding adapting works by other composers was the transcription of Gustav Mahler’s First symphony when Lühl was only fourteen years of age. Entitled “LWV 1”, it was reworked and corrected several years later. He spent six months at least transcribing it. This work gave him the necessary basis for his future studies in orchestration and writing. A great admirer of the composer from a young age, he never stopped working on transcription projects of Mahler’s other symphonies, especially the Fifth one.

Genesis of the original piano quartet by Mahler (first movement)

For this chapter, let us cite Henry-Louis de La Grange in his

masterwork on Mahler’s life1. Mahler entered the Vienna

conservatory in 1875 and had already composed a certain number of

pieces for chamber music and Lieder : “Without a doubt, during his

second year at the conservatory, Mahler shared during two months a

student room with [Hugo] Wolf and Krzyzanowski2. All three lived

in harmony and played each other’s most recent works. It seems

Wolf considered his Lieder inferior to his two friend’s works3. In

one night, Mahler composed on the piano a quartet movement for a

competition at the conservatory, while the other two were obliged

to go and sleep on the banks of the Ring4. […] Mahler composed

continuously for the conservatory and also for himself. Only small

fragments have survived this period, a movement for piano quartet

from 1876, the beginnings of a Scherzo for the same

instrumentation and two Lieder-fragments. […] The title page from

this quartet movement carries the mention ‘Clavier Quartett :

Erster Satz: Gustav Mahler ; 1876.’ Above the title was Theodor

Rättig’s seal, which suggests Mahler submitted the work to him in

1878, the year when Rättig published Mahler’s arrangement for

piano duet of Bruckner’s Third symphony.

As with many other manuscripts from his youth Mahler wrote

complicated arabesques and scribblings on the margins and on the

title page, as well as on sketches of the Klagende Lied.

The first movement and the unfinished Scherzo were published in

1973 by Peter Ruzicka at Sikorski publishers, Hamburg, Germany

[the score which Lühl worked on for his research].

The fact that the sketches of the Scherzo were in the same file

seems to indicate they consisted of two parts of the same work.

However, it is most unusual for a conservatory student to compose

a Scherzo in g minor for a work normally written in a minor.

In the first movement, the score is clear and ordered. Only the

last three pages betray the composer’s haste. For the last bars,

the pianist’s left hand plays a long tremolo, upon which the young

man wrote hastily the word Orgelpunkt (fermata). The musician’s

obvious models for this school exercise were Schumann and Brahms,

which is not surprising, as Julius Epstein, his master at the

conservatory, was one of the first to interpret Brahms’s music for

piano and chamber music, and Franz Krenn and Robert Fuchs were

composition teachers well known for their observance of tradition.

The unfinished Scherzo

All the pieces from Mahler’s youth, Lieder and chamber music, were

lost or destroyed. Only a few fragments of unfinished pieces

survived which are kept preciously at the Mahler Library, in Paris

and Vienna.

In 1991, when Lühl was the same age as the master, he decided to

undertake a task which he pursued for several years: to complete

the second unfinished movement, to discover and make known what it

could have been. His musical knowledge was already confirmed,

thanks to extended and intensive studies in writing at major

French music academies. But he felt the need to compose a sequel

to the original in the young Mahler style. He listened to a trial

version by the Russian composer Alfred Schnittke, which

disappointed him a lot; not because of the work’s quality, but by

the esthetic direction taken by the latter. Schnittke didn’t

consider trying to find the original style of the Viennese master:

he took the few existing sketches from the beginning of the work

and continued it in his own style.

Determined to remedy this, Lühl decided to begin a thorough

musical reworking of the sketches. He took those published by

Sikorski in the printed version and the manuscript fac-simile of

the original first movement. The manuscript text was almost

unreadable. Mahler, writing very quickly and interpreting his own

pieces, inserted shortcuts of all sorts to avoid useless

repetition. He sometimes wrote the main voice for an instrument

for which it had not been destined originally. Notes which didn’t

match correctly, incomplete chords, empty bars, all this was

fairly usual in the young composer’s writing style and made the

editor’s work in the transcription very difficult. For more

authenticity Lühl went to the Gustav Mahler library in Paris to

consult the original manuscript in a reproduction, kept at that

time in the Pieront Morgan Library in New York, which was better

reproduced than Sikorski’s. In this work, Lühl found mistakes in

the retranscription by the editor. He recopied the sketches

himself to study more closely later.

The first original page was maintained in its entirety, even if

the impossible tonal jumps at the end of the page made the

transition to certain passages very difficult. The formula with

double quavers at the piano was originally written for the viola,

which is difficult to play and didn’t sound right. Every composer

knows there exists moments in his life as a young creator that he

has ideas without really knowing how to give them form as he lacks

the technical means for writing. With maturity he later acquired

this. However, to avoid losing precious material he wrote them

down in case he could use them later. These unusual tonal jumps

reflect the type of thinking in the creative process of Mahler ;

Lühl reused this passage in ostinato (played by the viola) for an

instrument better adapted to this type of accompaniment – the

piano. The imposing return of the main theme is in the spirit of

Mahler, even if this was written after blank bars on the

manuscript in a minor. Lühl repeats, after the chromatic

progression and the cadenza, the development of the first period

in the same kind of harmonic evolutions heard previously in the

first movement. The piano remains the instrument of accompaniment

and the chords echo in the edited imitations.

Lühl purposely avoided employing double quavers for strings,

because the first movement is not a virtuoso piece. However, in

order to create a link with the original first part of the

movement, where the sixteenth note plays an important part in the

accompaniment, he adapted them for piano by developing

additionally the sequence in imitations.

An insert from the first movement and a small wink at the choral

theme from the end of the second movement of the Fifth symphony

culminates the first part in a brief moment of apotheosis. The

‘Halt’ – stop – is in reference to Mahler’s musical tics. A

transition of three bars, a sort of echo between the different

instruments, recalls the sounds of horns in the preparation of the

Trio in the Scherzo of the First symphony. The Trio, the central

piece, is exclusively borrowed from the Lied n° 4, also composed

in the same tonality (e flat major). The sinuous effect of the

accompanying formulas at the piano reminds one of Mahler’s

preferences for music at fairs and fanfares. Abrupt changes in the

homonymous tones are typical of Mahler and used frequently in his

works (here e flat Major/minor after a cadenza). A little

expressive, freely performed passage at the violin is also taken

from the Lied n° 4 (from the Kindertotenlieder). Youthful works

are often considered by composers as a canvas for the more

elaborate works of his mature years. A short transition takes one

back to the shortened Scherzo. As in the first movement, it ends

on three pizzicato chords.

Two years later, in 1994, while Lühl was studying chamber music

with the violinist Jean Moullière at the Conservatoire National

Supérieur de Paris, he presented his work to his professor.

Interested in the original creative process, Moullière suggested

premiering the second movement in the context of an obligatory

performance for his students. Equally, Lühl made contact in a

letter dated February 1995 with the International Mahler society

in Vienna to show them his work.

The premiere of this second movement, and the performance of the

first obligatory movement, took place at the Conservatory’s

amphitheatre on March 7th 1994 at 5 p.m. – along with two other

chamber music groups playing Strauss and Brahms – with the

composer at the piano accompanied by other students. The cellist

arrived late and had not practiced his piece sufficiently, which

upset the young composer, who was going to present his first

chamber music work. From memory, his mother said : “a lot of music

professors came especially to listen to Lühl.”

Despite his efforts to validate his work, its reputation was

limited to some comments in student magazines and certain

specialized reviews in Vienna and the work remains forgotten

somewhere in the drawers of the Mahler Society.

In 1996, Serge Gut, a well known French historian and

musicologist, presented Mahler’s youthful works at the Sorbonne

within a student syllabus. Again it was Jean Moullière who took

the initiative of proposing the second movement of the piano

quartet to Gut. This time other students played the two works. To

Lühl’s great disappointment he wasn’t invited to the rehearsals

which could have proved important in interpreting the second

movement; nor was he invited at the end of the performance to come

on stage. “I really must be very talented to have so many problems

to be recognized while alive !” he thought ironically, thinking of

all his famous predecessors, who also were not acknowledged.

In 1997, the Mahler Society in Vienna published an article, which

featured the re-edition of the original first movement by the

publishers Universal Edition, Mahler’s editor, with an appendix of

his complete works with a preface by the pianist Manfred Wagner.

Despite Lühl’s efforts to contact the pianist, his endeavors were

in vain. He finished his music studies and started a career as a

pianist around a series of international competitions. However,

the desire to listen to his own music continued and he tried to

have his work performed. Lühl reached the conclusion : “It’s

easier to have your music played post mortem“, but he stayed

tenacious and inquired with other French and Austrian musicians

about the possibility of playing his music.

His membership of the International Gustav-Mahler-Society in

Vienna, dating from 1998, didn’t help in promoting his work. He

came up against closed doors between the Mahler libraries in Paris

and Vienna, each of them giving different versions of the origin

of the original fragment written by Mahler and for purists, a

reconstruction work by Lühl was considered unthinkable.

In 1998, Lühl understood a work could not be finished if it

weren’t complete. The saying goes – redundant from the beginning:

it becomes clear if you consider a quartet with piano includes in

general four movements, which at present contains only two. He

decided to furnish his reconstruction work by adding two other

movements, not only in Mahler’s style, but using several sketches

from remaining fragments of other works and adapting them in

Mahler’s youthful style and arranging them for piano quartet. He

composed the two movements in one night, almost dying from carbon

intoxication, because he worked by candle light in emulation of

the way Mahler composed.

The third movement, the slow one, takes its origin from sources in

Henry-Louis de la Grange’s book on Mahler (vol.3), in an appendix

at the end of the work where the author mentions the existence of

fragments of unfinished or “lost” works : “March 15th and 16th

1991, the RIAS orchestra of West-Berlin, Lawrence Foster

conducting, played the first performance of Gustav Mahler’s

Symphonic Prelude orchestrated by the Hamburg musicologist

Albrecht Gürschnig. According to the latter, it concerned the

orchestration of a manuscript belonging to the National Library of

Vienna whose first page title included the following mention :

Symphonic prelude, from a copy by a student of Bruckner’s, Rudolf

Krzyzanowski, dated 1876. The transcription for piano is from an

[orchestral] score by Heinrich Tschuppik. At the bottom of the

page, written later in pencil : possibly a work by Mahler, written

for an exam ? Krzyzanowski worked with Mahler on the transcription

for the piano duet of Bruckner’s Third (second version). Since

then, no trace has been found of the orchestral score which

Tschuppik transcribed for piano. His manuscript includes eight

pages with a double cover page for the six others, 16 music lines

and three blank pages. Certain passages were written down on three

lines with no indication concerning the original orchestration.

The whole thing is composed of 292 bars and the tempo indicated is

nicht zu rasch [not too quickly]. The piece begins by the theme

following the basses, accompanied by an ostinato, typically

Brucknerian5.”

The theme in permanent progression, starts with the cello, like

many examples in Mahler’s music, with a fourth interval which is

full of very expressive appoggiaturas. In the second part, more

lively in d minor, Lühl thought of the slow movement of the First

Symphony (the ‘frère Jacques’ refrain). The immense progression

recalls the detailed work by Mahler in the similarity of the

writing process. The ending brings a certain instability, equally

inspired by the first symphonic movement before returning to the

reprise, shortened and enriched in the culminating moment just

before the end.

The Finale

The third and fourth movements merge and are connected by a brief

introduction in the last movement. Lühl’s choice for the main

theme comes from de la Grange’s source : “At the death of Alma

(Mahler’s wife), two manuscript sketches not belonging to any

known work by Mahler, were included in his collection. Today they

are at the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York and the other is at

the Stadtbibliothek in Vienna. The two pieces were examined in the

1920’s by Alban Berg, who wrote a manuscript page on the subject,

confirming they belonged to no known work. According to him, the

blue pencil marks seemed to be written at the end of Mahler’s

life, which suggests he had the intention of reusing the sketches

at a later date. According to Susan Filler, who studied the

writing closely, as well as the paper used, the two sketches date

in fact from around 1900 and are only canvases, each one including

numerous variations of certain passages. The first sketch, for a

Presto in G Major (Mahler expresses in a note his intention of

transcribing the whole music in F) comprises three pages. However,

to preserve the tonal unity of the quartet, Lühl decided to

transpose this theme in A Major to complete the cycle of four

movements in a lively atmosphere conforming to the styles of the

time.

Everybody knows that composers quote and requote each other and

then complain sometimes with a certain frivolity and lack of

scruples. Mahler did not hesitate to use the same process by

noting the first lines which were going to become the theme of the

opening fanfare of the Fifth Symphony in the first movement of his

Fourth. This Rondo theme was reworked in a way to preserve the

juvenile freshness of Mahler aged 16. The other parts are

influenced by his Lieder cycle the Knaben Wunderhorn; he never

stopped using the themes in his first four symphonies, especially

for the present examples, the Third and Fourth symphonies. In the

second part, Lühl uses the accompaniment formula of arpeggios at

the piano and the harmonic evolution of the first movement,

without however quoting it directly. The last progression towards

the end reminds one strongly of the end of the Scherzo from the

first symphony and the succession of punctuated chords in A Major

recall the academic approach Mahler had to follow in his

Conservatoire training. Lühl saw in his own work a future message

to express through the work : this quartet should contain the

genesis of the Klagende Lied and the First Symphony which followed

some time later.

In December 1998 he presented his work on Mahler including his

transcriptions of the symphonies to Universal Edition. They told

him that since the appearance of the gramophone, such arrangements

were no longer fashionable and lacked public demand! There

followed several letters to different editors because he had

learnt the 25 years of Sikorski’s copyright had ended and it was

possible now to present a complete reedition of the four

movements. Only the Peters/Frankfurt edition showed any interest

in the project and from February 1999 a correspondence began

between the editor and the composer. This is when Lühl embarked on

an important work of research and analysis on his composition

procedure. He chose to write the missing movements and to complete

the unfinished Scherzo (in part rewritten from the structure and

stylistic borrowings and translated from German), by justifying

his choice and naming his sources, so that an editor as well known

as Peters would have no unpleasant surprises.

Some months later he received a presigned contract from Peters.

Weary, he submitted the contract to a lawyer to understand the

language which was unclear to the young artist. Peters only wanted

to publish the first and the second movement which would have had

as a consequence that the other two movements would remain

unpublished or in the best scenario another editor would someday

put it in his catalogue and so separate the work for which he had

been trying so hard to assemble in its entirety. Some months later

he received a letter from Peters publishers who withdrew the

offer. Really disappointed by this decision, Lühl continued his

tireless quest to find another editor and to validate this cursed

work, even if the fourth movement was performed as a fringe

programme at the Salle Pleyel in 1998.

In 2000-2001, Lühl followed a teaching course in the CefedeM, a

state academy for training future music teachers, during which

students had to present an original teaching project. He proposed

the performance of an entire quartet by Mahler which he finished

himself with some colleagues who were not used to this kind of

challenge. The pedagogical benefit was obvious for him and his

team and it allowed him to hear the four movements played in 2001

in a concert, ten years after he had completed it.

This premiere on which the group spent more time than necessary

decoding the manuscript with the objective of producing a

meticulous work, was very enriching for Lühl from a point of view

of teaching, because the group never had the opportunity to follow

in the footsteps of a composer with so many biographical elements.

This entire quartet was later performed in Lille in 2004 with Marc

Lys, also a teacher at the CefedeM, playing the piano and

accompanied by three other musicians.

Since then this work is just languishing in Lühl’s archives. All

other attempts of playing the piece failed. It was only thanks to

Polymnie, Sylvain Durantel and his ensemble (beautifully

rehearsed) that the quartet finally was played as an example. This

recording allowed its author to thoroughly revise his quartet,

taking out slips of pen from the four movements, not only for his

own work but also Mahler’s, especially slips in transpositions and

symmetry between the beginning and the end. His familiarity with

composing sixteen years later allowed him to have a more objective

view of the piece and he did not hesitate to change obvious

mistakes which had crept into the work.

Lühl’s felt he could not leave a spelling mistake in a poem “or

not point out a strange rhyme on the pretext that the composer

finds it interesting. There are only rare exceptions where I

allowed this. Tonal music is still more flawless, because

everything has to be justified. It’s not because something pleases

me that it is necessarily good. Music is an art which functions

without exception to strict laws. And it’s in fact the absolute

control of these laws and their rigorous application which allows

one to produce a masterpiece or not. Otherwise one stays an

amateur all one’s life. Writing is an indispensable tool which is

very difficult to integrate intellectually, because to obtain

perfect understanding one needs Time which unfortunately today is

lacking in our life. Man constantly confuses quality and intuition

; he includes his own personal style into the music. That is why

he prefers to create a discourse on art than art per se.”

Note by the author regarding the Mahler-Lühl Quartet (translated

from German)

It is the wish of everybody to know what a composer would have

created if Death had not taken him away. Unfinished works create

great intellectual frustration for the listener and for

musicologists. Besides it opens the narrow way which leads to the

world of infinite hypothesis. We would like to know more and hope

to find an explanation how the composer would have finished the

piece without ever being able to know the reply.

To appease this frustration it happens in the history of music

that students, friends or avid admirers of the dead artist accept

the delicate challenge of completing sketches and drafts, hoping

to suggest by this work that the composer is still living among

us. So was born Tchaikovsky’s Seven Symphony (S. Bogatryrieff),

Chopin’s Third concerto (J-L. Nicodé), Weber’s opera The Three

Pintos (by Mahler himself), Mahler’s Tenth Symphony (D. Cooke)…

and this piano quartet.

The premiere of the first movement (1876) was for a long time

doubted, but it was supported by a tradition which decided on this

date. The rudimentary way of writing and the sometimes unreadable

Mahler while young indicates that he wrote with the purpose of

performing his own works. When I listened to several

interpretations of this relic movement I noticed when comparing

all the versions that they differ not only in the interpretation,

but more technically by certain details in the writing. The

interpreters believed themselves obliged to correct such and such

a note [in the case of the interpreter who is not a composer, he

can only limit himself to a minimum of corrections – the author’s

note today] for more logic in the sense of musical phrases. So I

decided at age 16, like Mahler in his time, to put my musical

knowledge as a composer to the test and started cleaning the score

in a more thorough way. But this was not enough and I discovered

large pages of a second movement, of a Scherzo ! I equally

accepted this new challenge and had at my means less material than

the first movement ; the numerous notes were unreadable or

harmonically incomprehensible.

This is how I had the exceptional privilege to work with Mahler

himself through his work and I threw myself into the enormous

challenge of this young and promising Austrian composer.

In less than a week the Scherzo was finished and it had great

success at the Conservatoire National de Paris.

After some performances, I sensed something was missing. I wanted

to hear more ; I wanted to make a complete quartet from the two

movements, a quartet ‘à la Gustav Mahler’ which sounds like Mahler

to the very last note. And so were born very quickly the third and

final movement and I hope that I lived up to the expectations of

this task: to develop and increase the young creative source of

Mahler’s musical evolution in homage to a man I admire and respect

enormously.

Enguerrand-Friedrich Lühl, Paris, Spring 1999

ENGUERRAND-FRIEDRICH LÜHL • PIANO QUARTET LWV 121

This work has a disappointing background story; normally, the

amateur music lover imagines ultra-romantic scenarios as the

source of inspiration for a musical work. In this case we have to

disappoint readers and listeners of this CD because the quartet

was composed practically with the single intention of being a

filler for this CD with the Mahler-quartet. Lühl didn’t leave any

other chamber music work with piano and this standard

instrumentation went very well with what he had planned to

complete his catalogue of works. Composed in nine days, including

the instrument material, in 2008, the quartet precedes his string

quartet n°5.

Lühl is a traditional composer: he avoids composing for occasions

and certain ensembles: “I’ve always thought that works which will

last for centuries were those of classical form and structure. In

musical literature we remember masses, symphonies and concertos,

sonatas and string quartets. Duos for flute and bass clarinet,

accordion trios and other curiosities are reserved for a certain

public. I don’t have the time for this sort of experimentation ; I

gave a work to finish before leaving this earth and it has to be

connected, noble and personal, and not something that is a passing

or ephemerical commissions.”

The advantage of composing quickly results in one’s desire for

connectivity is better achieved, because it remains permanently in

the creative flux and does not disappear until the project has

been finished. And so he had the idea of inserting a new musical

form; the second movement is inserted in the third one; until now

this is nothing exceptional, if only from a point of view of

structure, the two movements are in fact one and the slow movement

is in reality the central part of the Scherzo. The two movements

create a long fresco and the two themes, apparently radically

opposed by speed and atmosphere are in fact closely linked by the

construction.

The finale, a rondo, takes up in the couplets quotations from the

other movements in chronological order. The impression given when

listening to this quartet is that of a voyage without halts,

despite the few interruptions (or ‘false’ interruptions) between

and during the movements.

KONZERTSTÜCK LWV 19

This crazy and brilliant piece for all the instruments is an

arrangement of a study for piano. Its style reminds one of an

encore, ideal to finish a serious and fundamentally romantic

musical soirée. Its author has equally arranged this study for two

pianos (“Konzertetüde LWV 145”), a not less virtuoso and startling

piece.

This CD presents for the time being the only pieces which Lühl

wrote for piano quartets. Others may follow, according to

inspiration.

CD 2

GUSTAV MAHLER

SYMPHONY n° 1 “Titan” for piano solo

“Transcription of Mahler’s First symphony for piano LWV 1” is the

text appearing on the manuscripts front page, Lühl’s first opus.

Six months of relentless work for the young musician, thanks to

which he learnt the essentials of orchestration and

instrumentation techniques, well before he started his harmony

lessons with Bernard de Crépy, a professor at CNSM/Paris. It was

an enriching undertaking from many points of view, because he

worked in the old fashioned way, using an indelible pen and

writing on a magnificent copy book for composition, especially

created by a book-binder for this occasion. It was obvious,

knowing the graphic attention that he brought to the editing of

his works that this score was thought of as a synthetic and

intellectual work, not particularly destined for stage

performances: crossed out bars of music, sloppy handwriting and

overlapping of passages to be played “by choice”, according to the

size of the hand, was left to the discretion of the performer. In

the last movement, the figure 52 at the spectacular repeat of the

final fanfare, Lühl notes for example in the page’s margin : “In

the first movement, during four bars, one can play trumpets (the

melody above or below the octave) and get rid of the tremolos.”

Such remarks are frequent and show the worry of being as exact as

possible when playing with the full orchestra.

Lühl was already passionate about the inheritance of the Viennese

master at the age of ten, when he had started playing piano with

his mother one year previously. She was a fine teacher and an

amateur pianist. The professor Michal Carcassone, a surgeon in the

pediatric hospital in Marseille, had shown in 1987/88 to the young

musician his impressive collection of scores. Although not a

musician he had collected a precious catalogue of works in part

out of print. Among those figured the nine symphonies of Mahler

for piano duet. Lühl was fascinated by the quality of the editing

work and he planned the transcription of the whole collection of

Mahler’s symphonies. Decided to start this titanic work, which

could honor its original composer, he was persuaded that even

today some of Mahler’s work were unappreciated by the greater

public, because of continuously programming the last symphonies in

public and ignoring the earlier ones, infused with a very sharp

and dissonant tonal language which was difficult to listen to.

Therefore, he planned to transcribe the ten symphonies for piano

solo on his own. He was convinced that no arranger had taken the

trouble to do this before. Everybody wasn’t Liszt, who transcribed

for piano solo all Beethoven symphonies. Finally the project

stopped after the first symphony, judged too great in relation to

his own compostions. He bought a pocket score and set to work

straight away. He composed at the piano, noticing very quickly

that a faithful adaption needed more than just a plain

transcription of all the orchestral voices: he had to give the

piano its orchestral mass, which one could only obtain by changing

certain aspects of the original text: heights, dynamics,

superimposition of different voices, by order of acoustic

priority… The symphony is full of very long passages where the

basses have prolonged notes. Lühl discovered the use of the

“tonal” pedal, which allowed him to resonate certain blocked keys

and to cleanse the music with repeated changes in the forte pedal.

We see for example on the manuscript the frequent mention in

French: “Keep central pedal down, but repeat the C key” (fourth

movement, number 41). The end of the first movement is illustrated

by a photocopy of a known photo of Mahler taken in 1888, a date

around in which he composed his colossal work. The last page

finishing the transcription is dated : “August 20th 1990”.

Contrary to his previous habit, the date is written in French.

It’s only eight years later, in November 1988 that he decided that

the transcription would have a better future than that of a simple

writing exercise which would finish in a drawer. Under catalogue

number 49 he rewrote all the score with his more advanced

knowledge and added the orchestral effects sought after in vain at

the time before, lacking piano and composition techniques. Lühl

considers today that his work begins really with his second opus,

the unfinished Mahler-quartet, and that the first one was just a

warm up. His real version, presented here, is from 1988. One finds

the usual graphic care with which he writes his scores.

![]()

En écoute : Mahler, Quatuor avec piano, Scherzo

![]()

Accueil | Catalogue

| Interprètes | Instruments

| Compositeurs | CDpac

| Stages | Contact

| Liens

• www.polymnie.net

Site officiel du Label Polymnie • © CDpac • Tous droits

réservés •