|

|||||

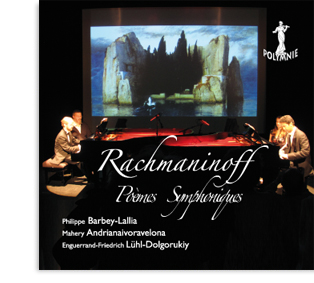

Rachmaninoff Poèmes

Symphoniques

Oeuvres

originales pour deux pianos

Philippe Barbey-Lallia, Mahery Andrianaivoravelona,

Enguerrand-Friedrich Lühl-Dolgorukiy, piano

POL 151 481

Rachmaninoff

Poèmes Symphoniques

Aleko, Danse des femmes *

Aleko, Danse des hommes *

Le Rocher *

Caprice bohémien *

Vocalise *

Isle des morts *

Danse symphonique 1

Danse symphonique 2

Danse symphonique 3

* premier enregistrement mondial

LES POEMES SYMPHONIQUES

Deux Danses extraites d’Aleko

Pour l’examen final du Conservatoire, Rachmaninov devait composer

un opéra en un acte sur un poème de Pouchkine, Les Tziganes. Il

écrivit son premier opéra en une vitesse incroyable de dix-sept

jours. L’approbation du jury fut unanime et Rachmaninov obtint en

1892 la Grande Médaille d’or du Conservatoire avec une année

d'avance (cette médaille ne fut attribuée qu'à deux autres

étudiants dans l'histoire du Conservatoire). Si Aleko reçut un

accueil enthousiaste et les hommages de Tchaïkovski (durant la

première, au Bolchoï, le compositeur russe applaudit

ostensiblement), il fut plus tard rejeté par le compositeur,

jugeant sa structure "à l’italienne " démodée. Composé de treize

numéros, il en arrangea les Deux Danses de ballet pour deux pianos

de manière assez libre, en ajoutant des parties ossia pour

amplifier l’arrangement.

Vraisemblablement, la partie centrale lancinante de la Danse des

femmes sera reprise dans une des quatre improvisations que

Rachmaninov écrira quatre ans plus tard avec ses professeurs et

mentors Arensky, Glazounov, et Taneïev. Ces deux danses ne sont

pas sans rappeler une œuvre bien plus connue du même auteur, qu’il

écrira à la toute fin de sa vie, les Danses symphoniques, et il

est émouvant de s’imaginer qu’il commence et termine sa vie de

compositeur avec des danses, alors qu’il n’en n’écrira

pratiquement pas dans l’intervalle de ces deux extrêmes.

Le Rocher op.7

Comme dans son premier poème symphonique, Prince Rostislav, écrit

sans numéro d’opus (dont il n’existe pas de transcription par

l’auteur), Rachmaninov s’inspire de sources littéraires. L’œuvre

est précédée d’une citation de Lermontov extraite du poème du même

nom :

« Un petit nuage doré a sommeillé Sur le sein d’un rocher géant. »

Ces deux lignes avaient servi d’épigraphe à la nouvelle de

Tchekhov Pendant le voyage. L’histoire relate la rencontre entre

un homme d’âge mûr et une jeune femme dans la salle d’une auberge

pendant une tempête de neige. L’homme raconte à la femme les

déboires de son existence. Les personnages sont représentés par

deux leitmotivs : le premier, sombre et lugubre, aux cordes

graves, le second, un motif insouciant à la flûte. Rachmaninov

acheva la partition d’orchestre pendant l’été 1893, et

Tchaïkovski, impressionné par l’ampleur de l’œuvre, comptait la

diriger la saison suivante. Sa mort prématurée l’en empêchant, ce

fut Vassily Safonov qui en fit la création en avril 1894.

Caprice bohémien op.12

Rachmaninov avait remporté une belle récompense avec son opéra

Aleko en 1892. A cette date, il avait fait la connaissance de la

chanteuse bohémienne Anna Lodizhenskaya et de son époux Pyotr qui

devint le dédicataire de cette nouvelle partition (Anna recevra un

peu plus tard une dédicace sur la partition de la première

symphonie). Entre 1892 et 1894, il travaille à sa nouvelle pièce,

incluant quelques citations et allusions aux motifs de son opéra.

En raison de la longueur considérable de l’œuvre, Rachmaninov

permit, comme dans d’autres œuvres telles que le Troisième

Concerto, des coupures ne nuisant pas à la continuité du discours

musical. Dans cette version transcrite par l’auteur, la partition

est interprétée dans son intégralité.

Vocalise op. 34 n°14

Qui ne connaît pas cette merveilleuse romance pour voix et piano

de Rachmaninov ? De nombreuses adaptations ont été réalisées pour

les formations les plus diverses, allant du piano solo au duo

violon/piano ou violoncelle/piano, trio et même chœur mixte !

Cependant, Rachmaninov avait réalisé lui-même, tout comme pour le

Prélude op. 3 n°2 (POL 150 865), une version pour deux pianos

extrêmement complexe quant à la densité de son écriture.

L’équilibre des voix est parfait et l’arrangement nécessite une

grande recherche sur la profondeur du son. Rachmaninov, suite au

succès populaire de sa romance, adapta également cette pièce pour

orchestre et l’enregistra le 20 avril 1920 avec le Philadelphia

Orchestra.

Isle des morts op. 29

"Je travaille maintenant beaucoup, mais je voudrais pendant le

dernier mois qui me reste avant mon retour à Moscou, travailler

encore plus. Mon avis sur les nouvelles œuvres est toujours le

même, c'est- à-dire : je les termine avec peine et je suis

insatisfait de moi. C’est un supplice constant." Alors que sa

Deuxième Symphonie op. 27 venait juste d’être terminée, le séjour

de Rachmaninov à Dresde s’avéra encore plus productif avec la

première Sonate pour piano op. 28 de plus de quarante minutes et

l’Isle des morts, poème symphonique reprenant la conception

orchestrale de Liszt sur support littéraire et pictural.

Rachmaninov eut entre les mains une reproduction en noir et blanc

du tableau du peintre suisse Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901) "die

Toteninsel" (1883, Berlin, Nationalgalerie). Après l’avoir vu

l’original plus tard, il s’exclama : "Je n’étais pas

particulièrement ému par la vue du tableau en couleur. Si j’avais

vu l’original en premier, je n’aurais vraisemblablement jamais

écrit l’Isle des morts." Rachmaninov ouvre la dimension

symphonique sous un nouvel aspect, très difficile à réaliser du

point de vue de la composition : l’œuvre est d’une homogénéité

d’ambiance rare et les différentes périodes s’enchaînent comme par

magie avec une fluidité incomparable.

Léopold Stokowski écrivait à Rachmaninov le 18 mars 1933 :

"En me plongeant dans l’Isle des morts en vue de ces concerts,

j’ai été profondément impressionné par son unité stylistique et

formelle. Sa force métaphysique ne m’a jamais paru aussi grande,

mais surtout je n’avais jamais mesuré la perfection de sa

structure. Cela se déploie depuis les racines, jusqu’aux branches,

aux feuilles, aux fruits – exactement comme un arbre, ou comme la

musique de Bach. "

De plus, Rachmaninov y insère les premières notes du Dies Irae,

chose qu’il fit un certain nombre de fois dans ses œuvres

postérieures. Quoi de plus naturel que de l’insérer dans une œuvre

avec un titre comme celui-ci ! On a donné deux raisons de la

puissante attraction exercée par ce chant sur Rachmaninov, qui le

poussa à y revenir à plusieurs reprises dans d’autres œuvres. Les

uns assurent que Rachmaninov voyait dans le Dies Irae une sorte de

memento mori et qu’en dépit du sinistre présage qu’il évoquait, il

exigeait qu’il dépensât beaucoup d’activité de son vivant.

D’autres pensent que les sombres préoccupations où le jetait le

mot "destin "amenèrent Rachmaninov à conclure que c’est par la

mort seule qu’on peut le surmonter. Cette perpétuelle idée de la

mort peut toutefois avoir été la réaction provoquée par le

sentiment qu’il avait "terriblement vieilli" et il était terrifié

à la pensée "qu’il allait bientôt rejoindre le diable ". Alors il

tomba brusquement dans une dépression qui dura des semaines et se

manifesta par de l’apathie, de la répulsion pour tout ce qu’il

avait fait, et pour "tout le reste aussi". L’acharnement avec

lequel il écrivait lui causait des troubles de la vue et il

souffrait de migraines. Il dormait mal et se plaignait de

"décoller ". "J’ai une douleur à un endroit et c’est ailleurs

qu’elle me fait souffrir."

Il est intéressant de noter que Rachmaninov a enregistré le Poème

Symphonique aux Etats-Unis le 20 avril 1929 sans les quatre

premières mesures d’introduction. La pièce débute dans les tons

plaintifs et désespérés. Le mouvement irrégulier de la formule

d’accompagnement dans les graves rappelle les coups de rame que le

batelier, Charon, donne à l’onde tranquille pour conduire la

silhouette blanche se tenant debout sur la barque. Le passage

central est beaucoup plus animé et même virulent. Rachmaninov

disait de ce passage : "Il doit y avoir un contraste puissant avec

tout le reste. Ce passage doit être plus rapide, plus agité et

passionné et être interprété en conséquence. Comme ce passage ne

fait pas référence à l’œuvre, il s’agit ici d’une sorte de rajout

; c’est pour cela que ce contraste est indispensable. D’abord la

mort, ensuite la vie. "C’est dans cet esprit que Lühl écrivit son

Requiem à la mémoire du Maréchal de Vauban (réf. Polymnie

790 344). La musique est une résurrection du personnage : le

passage central de l’Isle des morts peut également refléter les

tristes souvenirs de cette silhouette conduite par le batelier sur

l’île. La transcription d’Otto Taubmann date de 1910 et fut écrite

à l’origine pour 4 mains, selon la tradition classique de

l’arrangement d’une œuvre orchestrale pour clavier. C’est sur

cette base que fut réalisé le présent enregistrement, Lühl l’ayant

amplifié en ajoutant les voix manquantes de l’orchestre, ce qui

donne à la version 4-mains le volume symphonique nécessaire pour

gagner en effet de masse.

Danses symphoniques Op. 45

Le premier véritable témoignage sur les Danses symphoniques pour

deux pianos op. 45, nous est parvenu par une lettre du 21 août

1940 de Rachmaninov à Eugène Ormandy, alors chef du Philadelphia

Orchestra : " La semaine dernière, j’ai achevé une nouvelle pièce

symphonique, que je voudrais bien sûr vous donner en premier, à

vous et à votre orchestre." La création orchestrale eut lieu à

Philadelphie le 3 janvier 1941 sous la baguette d’Ormandy. Quant à

la version pour deux pianos (composée avant l’arrangement

orchestral), la première eut lieu à Beverly Hills en petit comité

chez le compositeur avec Vladimir Horowitz au deuxième piano. La

partition porte l’annotation en russe du compositeur "10 août 1940

Long Island". De plus, il nota en anglais " I thank Thee, Lord.",

témoignage envers sa profonde croyance en le Seigneur.

La partition d’orchestre fut achevée à la fin du mois d’octobre de

la même année à New York et fut publiée par Charles Foley en 1941.

Rachmaninov s’était établi avec sa famille à Beverly Hills, très

exactement au 610, Elm Drive, dans une magnifique villa à la

façade et au portique bombés. Un garage abrité sur la gauche y

accueillait ce qu’il appréciait le plus : les voitures rapides et

puissantes."C’est ici que je mourrai", disait-il.

Les Danses symphoniques naquirent apparemment avec l’idée qu’elles

seraient la dernière œuvre de leur créateur. En effet, les

citations d’œuvres antérieures sont étonnamment fréquentes :

Première Symphonie (thème principal), les Vêpres, et encore une

fois le Dies Irae dans la dernière danse, un dernier essai de

rendre gloire à la patrie perdue ? Les titres originaux (Matin,

Midi et Crépuscule) ont été remplacés par Midi, Crépuscule et

Minuit, selon ce qu’il prétendait de lui : "Je suis un pessimiste

de nature." 6 Les trois danses sont des références à d’anciennes

danses revisitées avec le style très personnel du maître : marche,

valse et tarantelle. Rachmaninov, l’expatrié déchiré entre confort

opulent au quotidien et cœur brisé dans son identité nationale,

suivait avec grand intérêt les nouvelles du front et donna même un

concert caritatif pour l’Armée Rouge, alors que la politique du

régime l’avait forcé à quitter en 1917 son pays dans l’affolement.

La saison 1942-43 fut la dernière au cours de laquelle joua

Rachmaninov. Elle marquait la cinquantième année de sa carrière de

concertiste et il approchait de son soixante-dixième anniversaire.

Les quelque 120 concerts par an qu’il dut produire en continu en

Europe pendant des années laissèrent des traces indélébiles sur sa

santé : il se sentait usé et ne joua plus que son ancien

répertoire. Le manque de temps pour composer se faisait ressentir

de plus en plus et il mit toute son énergie dans ce qui allait

être sa dernière œuvre. Il avait formé le projet, à l’issue de sa

tournée, de se retirer en Californie dans sa nouvelle maison. Ses

amis insistaient pour qu’il se consacrât à la composition mais il

répondit : " Ce qu’il y a de pire, c’est la peine que me coûtent

ces concerts, mais que serait la vie sans eux, sans musique ?

[...] et puis je suis trop fatigué pour composer. Où voulez-vous

que je trouve la force et la flamme nécessaires ? [...] " "Mais

vos Danses symphoniques ? Comment avez-vous donc fait pour les

composer ? ", insistait un ami et admirateur. Rachmaninov avait un

faible pour cette dernière œuvre, peut-être parce que c’était son

ultime création. " Je ne sais pas comment ça s’est fait, répondit-

il. Cela a dû être une dernière étincelle ..."

Le manuscrit des Danses symphoniques dans les deux versions est

désormais conservé à la Library of Congress de Washington DC. Pour

cet enregistrement, Lühl a rajouté les voix manquantes de

l’orchestre, fidèle à sa conception orchestrale d’interprétation

pianistique.

![]()

Two dances from Aleko

For the final conservatory examination Rachmaninoff had to compose

an opera in one act on a poem by Pushkin, the Gypsies. He wrote

his opera in an incredibly short time of seventeen days. The

approval of the jury was unanimous and Rachmaninoff obtained the

conservatory’s Gold Medal in1892. This reward was only given to

two other students in the conservatory’s history. If Aleko was

enthusiastically welcomed by Tchaikovsky during the premiere at

the Bolshoi (the Russian composer applauded loudly) it was later

rejected by the composer who judged its structure as out of date

and too “italian”. Composed in thirteen sequences, he arranged two

ballet dances for two pianos in a fairly liberal manner by adding

two ossia parts to emphasize the arrangement. Probably the central

sensual part of the women’s dance would be taken up again in for

improvisations which Rachmaninoff wrote four years later with his

professors and mentors Arensky, Glazunov and Taneiev (POL 151

375). These two dances recall another well known work by the same

composer that he would write at the end of his life: the Symphonic

Dances op. 45 and it is moving to imagine that he started and

finished his life as a composer of dances, although he hardly ever

wrote any during the interval.

The Rock op.7

Like his first symphonic poem Prince Rostislav, written without an

opus number (which does not exist in an arrangement for piano duet

by the author), Rachmaninoff was inspired by literary sources. The

work is preceded by a quote by Lermontoff, an extract from the

poem of the same name :

“A little golden cloud slept On the breast of giant rock.” These

two lines served as an epigraph in Chekhov’s novel During the

voyage. The story talks about the meeting between a man of mature

years and a young woman in a tavern during a snow storm. The

characters are represented by two leitmotivs: the first dark and

heavy, played by cellos and double basses, the second in a

nonchalant motive by the flute. Rachmaninoff finished the

orchestral score during the summer of 1893 and Tchaikovsky,

impressed by the work’s gravitas, planned on conducting it the

following season. Unfortunately

his premature death stopped it and it was Vassili Safonoff who

premiered it in April 1894.

Caprice bohémien op.12

As said above, Rachmaninoff won an award with his opera Aleko in

1892. At this time he met the bohemian singer, Anna Lodizhenskaya

and her husband Pjotr, to whom he dedicated this new score.

Rachmaninoff later dedicated his first symphony’s score to Anna.

Between 1892 and 1894 he worked on a new score including some

quotations and allusions to themes from his opera. Because of the

work’s considerable length Rachmaninoff allowed, as in other works

(such as the Third piano concerto) two little edits which do not

affect the continuity of the musical discourse. In this

arrangement, transcribed by the author, the score is interpreted

in its entirety.

Vocalise op.34 n°14

Who does not know this wonderful romance for voice and piano by

Rachmaninov? Numerous adaptations have been made for the most

diverse formations, from solo piano to duet violin/piano or

cello/piano, trio and even mixed choir. However Rachmaninov

composed himself like for the prelude op. 3 n°2 (POL 150 865) an

extremely complex version for two pianos when it comes to the

quality of his composing. The balance of roles is perfect and the

arrangement necessitates great research for interpretation.

Rachmaninov, following the popular success of his romance equally

adapted this piece for orchestra and recorded it on April 20th

1920 with the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Isle of the Dead op. 29

"I’m working a lot at the moment but I would like to work more

during the last month before my return to Moscow. My opinion of

the new pieces is still the same, which is to say I finished them

with great difficulty and I am still dissatisfied with myself.

It’s a painful experience." When his Second Symphony op. 27 was

just finished, his stay in Dresden had proved to be very

productive. The first Sonata for piano op. 28, which lasts more

than forty minutes and the Isle of the Dead, a symphonic poem

repeating the orchestral concept by Liszt on the background of a

literary and pictorial source.

Rachmaninoff saw a reproduction of a black and white painting by

the Swiss painter Arnold Böcklin (1827- 1901) "die Toteninsel"

(1883, Berlin, Nationalgalerie). After seeing the original later,

he exclaimed: "I wasn’t particularly moved by the original

painting. If I had seen it at first, I would never have written

The Isle of the Dead. "

Rachmaninoff begins the symphonic dimension under a new aspect,

very difficult to achieve from a point of view of composition: the

work is set in a rare homogeneous atmosphere and the different

periods are linked as by magic by an incomparable fluidity.

Leopold Stokowski wrote to Rachmaninoff on March 18th 1933:

"Immersed in the Isle of the Dead with these following concerts in

mind, I was greatly impressed by the stylistic and formal unity of

the piece. Its metaphysical force never seemed so great to me,

especially as I had never considered the perfection of its

structure. This begins right from its roots to its branches, to

its leaves, to its fruits – exactly like a tree or like Bach’s

music."

Also Rachmaninoff inserted the first notes of Dies Irae,

something he will do a certain number of times in his future

works. What is more natural than to insert it in a work with a

title like this! Two reasons are given for the strong attraction

as to why this song so influenced him and why he used it again in

several works. Some say Rachmaninoff saw in the Dies Irae a

‘momento mori’, a sort of time of Death, and despite the gloomy

prediction which he evoked he demanded of himself lots of work as

long as he was living. Others say that the dark preoccupation

where he threw himself into the word ‘Destiny’ brought

Rachmaninoff to the conclusion that only Death can overcome Fate.

This perpetual idea of Death could have been a reaction caused by

the feeling that he had aged terribly and that he was terrified by

the idea that soon he was going to meet up with the Devil. When he

suddenly fell into a deep depression which lasted weeks and

manifested itself by great apathy, by the disgust he had for

everything that he had written and for all the rest as well, the

compulsion with which he wrote caused him eye problems and he

suffered from migraines. He slept badly and complained about

hallucinating. “I have a pain somewhere and it’s elsewhere that I

suffer.”

It’s interesting to note that Rachmaninoff had recorded the

Symphonic Poem in the United States on April 20th 1929 without the

four first introductory bars of music. The piece begins in

plaintive and despairing tones. The irregular movement of the

accompanying formula in the lower notes reminds one of the oars

stroke that the boat-man Charron adds to the quiet lake’s waves in

order to bring the white figure standing in the barge nearer to

the island.

The central core is much more animated and even virulent.

Rachmaninoff said about it: “There has to be a strong contrast

with the rest of the piece. This passage must be quicker, more

agitated and passionate and must be performed accordingly. As this

passage is not a reference to the painting, it is a sort of a

post-scriptum. That is why this contrast is absolutely necessary.

First Death, then Life.”

It is in this state of mind that Lühl wrote his Requiem in memory

of Marshall de Vauban (Polymnie 790-344): the music is a

resurrection of the Marshall. The central part of the Isle of the

Dead can also reflect the sad memories of this figure being taken

by the boat-man to the island. The Otto Taubmann transcription

dates from 1910 and was written originally for piano duet,

according to the classical tradition of the arrangement of an

orchestral work for piano. Based on this the present recording was

done, Lühl having updated it by adding the missing voices from the

orchestra which gives the duet the symphonic dimension, necessary

to achieve the mass effect.

Symphonic dances Op.45

The first real mention of the Symphonic Dances for two pianos op.

45 is in a letter from Rachmaninoff dated August 21st 1940 to

Eugene Ormandy, then leader of the Philadelphia Orchestra: “Last

week I finished some new symphonic pieces that I want to be sure

to give to you before anybody else, to you and your orchestra.”

The premiere took place in Philadelphia on January 3d 1941

conducted by Ormandy. Regarding the two-piano-version, composed

before the orchestral arrangement, the premiere took place in

Beverly-Hills for a small group of friends at the composer’s home

with Vladimir Horowitz playing the second piano. The piece is

dated in Russian by the composer: “August 10th 1940, Long Island.”

He also wrote in English: “I thank Thee, Lord”, a sort of witness

to his belief in God. The score was finished at the end of

October, the same year in New York and was published by Charles

Foley in 1941. Rachmaninoff had set up home with his family in

Beverly-Hills at 610, Elm Drive in a magnificent villa. The garage

on the left had his collection of very powerful cars. “I will die

here”, he said.

The Symphonic Dances were created with the idea they would be his

last pieces. He quotes musical passages from this previous works:

First Symphony (main theme) and the Vespers, and once more the

Dies Irae in the last dance, a final chance to pay homage to the

lost country, Russia? The original titles (Morning, Noon and

Evening) were replaced by Morning, Evening and Midnight, with the

remark that he made about himself: “I am a pessimist by Nature.”

The three dances are references to previous ones revisited with

the personal touch of the master: a march, a waltz, a Tarantella.

Rachmaninoff, the ex-patriot, torn between the opulence of

every-day life in America and his broken heart for his national

identity, listened with great interest to news from the front and

even played a concert in benefit of the Red Army, even though the

regime’s politics had forced him to leave his country in 1917. The

season 1942-43 was the last in which Rachmaninoff performed as a

pianist. It was the 50th year of his career and he was approaching

his 70th birthday. The 120 concerts a year which he had to produce

continuously in Europe during years had now taken its toll on his

health. He felt worn out and only played his old repertoire. He

had less and less time for composing and put all his energy into

what was to be his last work. He had thought up the project,

during his tour to retire to California in his new house. His

friends wanted him to concentrate on composing, but he replied:

“What is worse is the prize I pay to play in these concerts, but

what would life be without music? [...] And anyway I’m too tired

to compose. Where do you think I will find the energy to do it?

[...]"“But your symphonic dances? How did you manage to compose

them? “, insisted a friend and admirer. Rachmaninoff had a

fondness for this last work, maybe because it was his ultimate

creation. “I don’t know how I did it”, he replied, “it must have

been the last spark.” The manuscript of the Symphonic Dances in

Rachmaninoff’s two versions is now kept in the Library of Congress

in Washington D.C. For this recording, Lühl added the missing

voices of the orchestra, faithful to his concept of orchestral

piano interpretation.

![]()

Philippe Barbey-Lallia, pianiste, chef d’orchestre

De nationalité franco-finlandaise, ce jeune chef d’orchestre a

débuté sa carrière en tant que pianiste concertiste. Après

plusieurs Prix de la ville de Paris à l’unanimité en piano et

musique de chambre, il a intégré le CNSM de Paris où il a obtenu

ses diplômes de pianiste concertiste et de musicien chambriste à

l’unanimité. Il y a reçu l’enseignement de Bruno Rigutto, Daria

Hovora, Claire-Marie Le Guay, Pierre-Laurent Aimard... Lauréat de

concours internationaux, il s’est produit à la Cité

Internationale, la Salle Cortot, la Maison de la Radio, au Palais

des Congrès, en la Cathédrale Notre- Dame de Paris, au Festival du

Vexin, au Festival des Nuits de Sainte-Anne à Montpellier, à la

Halle aux grains de Toulouse et au Musée des Jacobins... mais

également à l’étranger (Finlande, Grande- Bretagne, Allemagne,

Belgique, Irlande, Italie...). Depuis le premier concert qu’il a

dirigé à l’âge de 12 ans, Philippe Barbey-Lallia se destine à la

carrière de chef d’orchestre. Il a abordé l’écriture, l’analyse,

l’orchestration et la direction d’orchestre au Conservatoire du

Centre à Paris, avant d’entrer au CNSMDP dans la classe de Claire

Levacher. Il a participé aux masterclasses de Martin Lebel,

Olivier Dejours, Janos Fürst... Sélectionné par la prestigieuse

Académie Chigiana de Direction d’orchestre à Sienne, il a

travaillé auprès du maestro Gianluigi Gelmetti qui l’a nommé

lauréat de la promotion 2004. Depuis, il a été invité à diriger

notamment l’Orchestre Col Canto, l’ensemble Les Folies

Dramatiques, l’Orchestre des Lauréats du CNSMDP, l’Orchestre de

Sofia, l’Orchestre Symphonique de Mulhouse... Il est chef

titulaire de l’ensemble orchestral Ellipses, dédié à la création

d’œuvres de jeunes compositeurs, ainsi que de l’Orchestre

Cinématographique de Paris. Son talent avéré pour le répertoire

lyrique l’a amené à diriger plusieurs opéras d’Offenbach, Gounod

et Mozart, ainsi que Le Songe d’une nuit d’été de Mendelssohn et

le spectacle Viva Rossini sous l’égide de la fondation Rossini de

France.

Mahery Andrianaivoravelona, pianiste

Mahery Andrianaivoravelona s'est produit pour la première fois

comme pianiste avec orchestre à l'âge de 13 ans en interprétant le

9ème Concerto K271 Jeune homme de Mozart. En 1991, il entre au

Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris

(CNSMDP) dans la classe de piano de Michel Béroff et suit

parallèlement des cours de musique de chambre.

Il obtient quatre ans plus tard le Diplôme de Formation Supérieure

du CNSM de Paris, ainsi que diverses récompenses en histoire du

jazz, en acoustique, en déchiffrage et en analyse. Suite à cela,

il remporte divers Premiers Prix de Concours Nationaux et

Internationaux tels que ceux du Royaume de la Musique, du Concours

Claude Kahn ou encore du Concours de Saint-Nom La Bretèche et est

depuis invité à se produire en récital en France, en Allemagne

(Hattersheim/Düsseldorf), en Italie (Rome), en Tunisie (Hammamet),

à La Réunion, et dernièrement à Madagascar, à l'occasion de divers

événements, festivals, congrès médicaux ou pour des œuvres

caritatives (concerts au profit des victimes du cyclone « Geralda

» à Antananarivo, éditions 2002 et 2003 du Téléthon avec le COUPS

: Chœur et Orchestre de l'Université Paris-Sorbonne et à l'église

St-Merry).

Depuis 2004, il forme un duo avec le pianiste et compositeur

Enguerrand-Friedrich Lühl. Ce dernier, arrangeur pour piano solo

et deux pianos des œuvres de musique de films du compositeur

américain John Williams (déjà plus de 60 titres), prépare une

série de concerts en collaboration avec Musique et Toile, une

maison de spectacles événementiels spécialisée dans le cinéma,

autour des plus belles pages d’Hollywood, notamment avec «

l’intégrale Star Wars » pour deux pianos.

Toujours en collaboration avec Lühl, il participe sur plusieurs

années à une série d’enregistrements d’œuvres rares pour deux

pianos de Rachmaninov pour les éditions phonographiques Polymnie.

Parallèlement à son activité de concertiste, il mène régulièrement

une action pédagogique active à Madagascar au travers d'ateliers,

de Master Classes, de concerts et de jurys de concours.

Enguerrand-Friedrich Lühl-Dolgorukiy, pianiste, compositeur, chef

d'orchestre

Après avoir terminé brillamment ses études de piano à la Schola

Cantorum, Lühl complète sa formation en entrant à 15 ans au CNSM

de Paris. Trois ans après, il obtient un Premier Prix de piano à

l’unanimité. Parallèlement à son cursus de piano, il suit des

cours d’analyse musicale, de jazz, de musique de chambre, de

direction d’orchestre, d’harmonie et de contrepoint avec une

passion grandissante. Après ses études, il entre dans le monde

charismatique du Concours International et s’y consacre

pleinement. Dès 1998, il devient lauréat de plusieurs concours,

notamment Rome, Pontoise et le Tournoi International de musique.

Depuis, il fréquente les grandes scènes d’Europe (récitals,

musique de chambre, avec orchestre). La presse le qualifie

unanimement de concertiste international. Il travaille depuis 2005

pour le compositeur américain John Williams, pour lequel il

transcrit les partitions de ses plus grands thèmes de musique de

films pour piano seul et deux pianos. Il a enregistré en 2003 le

CD John Williams au piano vol. I avec ses propres arrangements des

plus grands thèmes d’Hollywood pour piano seul. Un deuxième volume

vient d’être enregistré avec les plus grands thèmes de Star Wars

pour deux pianos. Son catalogue de compositeur est conséquent :

six symphonies, deux concertos pour piano, de la musique de

chambre, diverses pièces pour soliste et orchestre, environ 120

pièces pour piano seul, des orchestrations et réductions, une

musique de film...

![]()

Philippe Barbey-Lallia,

pianist, conductor

Of French-Finnish nationality, this young conductor began his

careeras pianist concert performer. He obtained at CNSM of Paris

the diplomas of pianist and chamber music. He received the

teaching of Bruno Rigutto, Daria Hovora, Claire-Marie Le Guay,

Pierre-Laurent Aimard... International prize- winner of

competition, he play in the Cité Internationale, the Salle

Cortot, the Maison de la Radio, the Palais des Congrès, the

Cathedral Notre-Dame de Paris, to the Festival of Vexin, to the

Festival des Nuits de Sainte-Anne in Montpelier, in the Halle

aux Grains of Toulouse and in the Museum of the Jacobins but

also abroad (Finland, Great Britain, Germany, Belgium, Ireland,

Italy). Since his first concert at the age of 12, Philippe

Barbey-Lallia intends himself for conductor's career. He

approached the writing, the analysis, the orchestration and the

directionof orchestra in Paris with Claire Levacher, Martin

Lebel, Olivier Dejours, Janos Fürst, and Gianluigi Gelmetti on

the occasion of prestigious Chigiana academy of Siena. He

conduct the Orchestra Col Canto, the Folies Dramatiques, the

Orchestra of the Prize-winners of the CNSMDP, the Sofia

Orchestra, the Symphony Orchestra of Mulhouse, the Orchestra

Ellipses, and the Film Orchestra of Paris.

Mahery Andrianaivoravelona, pianist

Mahery Andrianaivoravelona first performed as a pianist with

orchestra at the age of thirteen when he played Mozart’s 9th

concerto K271. In 1991 he began his studies at the Paris

Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse (CNSMDP)

with Michel Béroff and at the same time followed courses in

chamber music. Four years later he received his diploma from the

CNSMDP as well as many awards in history of jazz, acoustics and

musical theory. After that he won various first prizes

nationally and internationally such as the Royaume de la

musique, the Claude Kahn competition and the international

Saint-nom-la-Bretèche competition. He has also played

internationally in France, Germany and Italy, Tunisia, La

Réunion and lately in Madagascar for festivals and special

events. Since 2004 he performs in duo with the pianist and

composer Enguerrand-Friedrich Lühl. The latter arranges for

piano solo and two pianos music from films and the American

composer John Williams (60 titles already). They are preparing a

series of concerts for Musique et Toile – a company specializes

in musical events for the cinema and around Hollywood

productions, in particular the Star Wars collection for two

pianos. Also with Lühl he has participated over the years in a

series of recordings of rare Rachmaninoff pieces for two pianos

for the Polymnie label.

In parallel to his activity as a concert pianist he organises

special music workshops for master classes, concerts and juries

in Madagascar.

Enguerrand-FriedrichLühl-Dolgorukiy,

pianist, composer, conductor

Enguerrand-Friedrich Lühl-Dolgorukiy was born in Paris in 1975.

He started his studies as a pianist at the Schola Cantorum then

completed his training by entering the Conservatoire National

Supérieur de Musique in Paris aged 15. Three years later he

obtained first Prize for piano. Parallel to his piano cursus he

studied music analysis, chamber music, orchestral conducting,

harmony and contrapoint. Since 1998 he has won several

international competitions and plays at prestigious venues

throughout Europe. The press is unanimous in considering him as

an international concert pianist. Since 2002 he has been working

with the production company Musique & Toile specialized in

the organisation of musical and film events for which he plays

his own arrangements for piano solo and duo of Hollywood’s great

film scores composed by John Williams. His 1300 pages of musical

arrangements will be edited at a future date. He also recorded a

CD entitled “John Williams’ music vol. 1” A second has just been

recorded with more great themes from Star Wars for two pianos.

His composer’s catalogue is impressive: six symphonies, two

piano concertos, chamber music, various pieces for soloist and

orchestra, around 120 original pieces for piano, orchestrations

and arrangements, film music.

![]()

![]()

Accueil | Catalogue

| Interprètes | Instruments

| Compositeurs | CDpac

| Stages | Contact

| Liens

• www.polymnie.net

Site officiel du Label Polymnie • © CDpac • Tous droits

réservés •