|

|||||

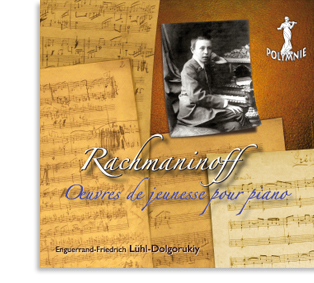

Rachmaninoff

jeune

Enguerrand-Friedrich

Lühl-Dolgorukiy, piano

POL 151 375

Commander

sur Clic Musique !

Sergueï Rachmaninoff

Nocturne n° 1

Nocturne n° 2

Nocturne n° 3

Suite en ré mineur

1er mouvement

2ème mouvement

Minuetto

4ème mouvement

Canon

Prélude en fa Majeur

Fugue en ré mineur

Romance*

Prélude en mi b mineur*

Mélodie*

Gavotte*

Improvisation 1*

Improvisation 2*

Improvisation 3*

Improvisation 4*

Morceau de fantaisie

Fugue en fa Majeur

Arensky

Fugue en ré mineur*

Lühl

Fugue sur le thème d'Arensky LWV 146*

* 1er enregistrement / first recording

"À partir de quand peut-on dire qu’une œuvre est un opus 1 ? "

C’est une question qui en tant que compositeur m’a souvent été

posée. Il est vrai que la décision d’un artiste de créer son

propre catalogue en y posant sa première pierre reste un mystère,

et rien en effet, à ma connaissance, n’a été écrit sur ce sujet si

subjectif.

À partir de quand donc, et surtout sur quelle base, ai-je décidé

d’appeler une œuvre ‘opus 1’ pour démarrer un répertoire qui

s’agrandira jusqu’à la fin de ma vie ? Est-ce la toute première

œuvre, lorsqu'on parvient à mettre des notes sur du papier de

manière à peu près cohérente, un bout de chiffon sur lequel on ne

reviendra plus jamais et qui moisira dans les tiroirs des

musicologues ? Ou est-ce plutôt l’expérience du jeune âge qui fait

qu’on croit avoir acquis suffisamment de ‘métier’ pour avoir conçu

une pièce de musique qui soit également jouable pour la postérité,

même s’il nous est impossible d’envisager ce ‘métier’ avec la

conscience professionnelle d’un adulte ? ou encore est-ce

peut-être l’envie de faire comme les grands, de faire des choses

abouties, le besoin de se sentir mûr et responsable d’une certaine

manière ?

Certains compositeurs revoient entièrement leur œuvre avant de

marquer un opus 1 digne de ce nom, d’autres se font aider pour

laisser à la postérité une œuvre de qualité malgré le manque de

métier patent dû au jeune âge ; d’autres encore ne mettront pas de

numéros du tout et laisseront un désordre incommensurable de

feuillets d’albums sans date ni référence. La méthode varie en

fonction de la personnalité de chacun. Pour ma part, j’ai eu

plusieurs opus 1 avant de décider que la transcription de la

Première Symphonie de Gustav Mahler pour piano seul à l’âge de

onze ans allait constituer le point de départ de ce qui allait

suivre. Je suis passé, comme tout le monde, par deux petites

feuilles avec des notes à peine esquissées, sans lien apparent

avec les autres, puis par une pièce pour piano quelques années

plus tard. Une autre vague de prise de conscience est venue et

l’opus 1 a encore été repoussé. Ce n’est que des années après,

pratiquement à la fin de mes études musicales, que mon catalogue

d’œuvres est devenu définitif, mettant un grand nombre de pièces

de côté en les détruisant ou en les reprenant, alors que je

m’étais juré, petit, de ne jamais reprendre quelque chose. Mais la

musique, comme l’art et tout le reste, est en mouvement et je dois

admettre que la seule chose qui compte pour une œuvre est sa

qualité pour en assurer la pérennité.

La plupart des compositeurs romantiques ont un dénominateur commun

: les opus 1 sont souvent de grandes œuvres (une Sonate en quatre

mouvements chez Beethoven, un Concerto chez Rachmaninov, une

Symphonie chez Stravinsky, et en ce qui me concerne, cette

transcription de la Première de Mahler…). Ce doit être un besoin

de se prouver quelque chose à soi-même, de commencer par un coup

de force directement pour être d’emblée immergé dans les sphères

de l’art, même si on ne parvient pas encore à toutes les saisir.

L’évolution du style musical personnel n’a pas de rapport avec la

qualité de la pièce, due à la maîtrise des outils techniques

d’écriture et de maturité musicales. Il ne s’agit pas de faire

d’une œuvre tonale de jeunesse une œuvre sérielle, sous prétexte

qu’on a évolué et que l’original est mal fait parce qu’il est

tonal. Tant qu’elle respecte les critères harmoniques et

contrapuntiques, les nécessités de structure et d’architecture, la

pièce reste néanmoins de qualité, même si le langage est

différent. C’est pour cela que, par exemple, Webern a maintenu

comme opus 1 son énorme Passacaille pour orchestre, qui est

foncièrement tonale et écrite dans un langage bien différent que

son opus 2 quelques mois plus tard. Les retouches que l’on peut y

apporter a posteriori sont d’abord d’un ordre technique, puis

esthétique. Nous devons apprendre à nous connaître nous-même pour

" trouver la mélodie qui est en nous " m’avait dit Henri Sauguet

quand j’étais tout jeune lors de notre unique entretien.

Ainsi, Rachmaninoff avait conçu son opus 1 le Concerto pour piano

n°1 de 1891 (qui ne vit sa forme définitive qu’en 1917 après de

sérieuses révisions) bien avant la version officielle de ce

chiffre. Les quatre pièces pour piano du premier opus 1 datent de

1887, alors que Rachmaninoff avait déjà composé un certain nombre

d'oeuvres tout aussi élaborées, complètes et personnelles, sans

qu’il s’agisse d’un exercice de style ou d’un devoir.

Les partitions éditées sans autorisation du compositeur ou de

l’héritier du temps de l’Union Soviétique sont imprimées sans

corrections et totalement dépourvues de nuances, d’indications de

variation de tempi et de phrasés. La première édition officielle

de certaines pièces aux éditions Sikorski ne m’a pas énormément

aidé, car elle n’a fait qu’épurer certaines lignes difficilement

lisibles et rajouter des phrasés, des indications de nuances et de

progression que le texte suggérait.

Il me fallut donc effectuer un travail passionnant de

reconstruction de la partition pour donner une architecture et une

organisation temporelle à chaque pièce. Ce que je connaissais du

style de Rachmaninov en tant que pianiste – je suis collectionneur

d’anciens enregistrements des compositeurs jouant leurs œuvres

depuis des années et ai la chance de posséder l’intégrale des

enregistrements du maître comme référence pianistique – , du

personnage après avoir longuement étudié sa biographie en

fouillant dans différentes archives pour trouver des raretés sur

sa vie et son œuvre, et ma qualité principale de compositeur,

stylistiquement très proche de Rachmaninoff, m’a permis de

construire un canevas d’interprétation cohérent – et surtout

plausible – autour de chaque pièce.

Curieusement, le jeune Rachmaninoff s’exprime très souvent dans

ses pièces autour de la tonalité de ré mineur. Dans ce disque,

nous retrouvons cette tonalité récurrente dans la suite et la

fugue. Ce serait peut-être dû au hasard, si on ne prenait pas en

considération les œuvres orchestrales ; à l’origine, la suite,

écrite pour orchestre, les poèmes symphoniques (Symphonie ‘de

jeunesse’, et le Prince Rostislav) ainsi que le Scherzo étaient

également dans la même tonalité.

Les Trois Nocturnes sont les toutes premières pièces de Rachmaninoff connues et ont été publiées illégalement par Muzgiz en 1949. Elles sont datées n° 1 du 14-21 novembre 1887, n° 2 du 22 au 25 novembre 1887 et n° 3 du 3 décembre au 12 janvier 1888. Dépourvues de nuances, ces pièces n’ont rien en commun avec l’ambiance planante et rêveuse des Nocturnes de Chopin. En effet, il m’a été difficile de m’imaginer la raison pour laquelle Rachmaninoff a nommé ces pièces ainsi, car cette musique n’a rien de ‘nocturne’, bien au contraire. La dernière page du troisième Nocturne a été perdue et les six mesures de fin sont une reprise du début, car il était impossible pour la pièce de se terminer sur le dernier point d’orgue.

La Suite en ré mineur est l’œuvre maîtresse de cette période. Le manuscrit d’une composition pour piano sans numéro d’opus a longtemps été préservé dans les archives du musée Glinka jusqu’en 1964 ; ensuite, l’œuvre a été transférée aux archives d’Alexandre Siloti. L’absence de page de garde indiquant un titre et le nom du compositeur, ainsi que la calligraphie de l’autographe ont rendu aux musicologues la tâche d’attribution particulièrement difficile. La période de création a ensuite été établie autour de ses années d’études au conservatoire. Dans une lettre datant du 6 janvier 1891, Rachmaninoff raconte à N. Skalon : "Depuis deux jours et demi, je n’ai pas arrêté d’écrire. Je viens juste de finir l’orchestration de ma Suite. Tout est bien, sauf qu’après l’avoir jouée au piano, ma main droite m’a terriblement fait mal…". Dans sa lettre du lendemain, il écrit : « Quant à ma Suite pour orchestre, je n’ai pas eu de succès : ils ne vont pas la jouer, car elle est écrite pour un orchestre symphonique qui contient des instruments que nous n’avons pas ici au conservatoire. Donc je vais devoir attendre l’année prochaine quand j’aurai trouvé une occasion pour organiser un concert tout seul, et je la jouerai alors. Je l’ai donnée à Tchaïkovski pour qu’il la regarde : je lui fais confiance implicitement pour tout. » L’histoire de la Suite reste cependant dans le flou. Une chose est certaine : les premières mesures d’ouverture rappellent étrangement le début du Prélude op. 3 n° 2 et surtout le début du Deuxième Concerto.

Les sources placent la date de composition du Canon, petite pièce de maîtrise (1ère pub. illégale par Muzyka en 1983), entre 1889 et 1892. Rachmaninoff a eu une période de grand travail contrapuntique pendant ses années d’apprentissage, pendant lesquelles il n’hésita pas à exploiter les acquis des cours de Taneïev et Arensky.

Le Prélude en fa majeur (20.7.1891) est la seule pièce à avoir été reprise par son auteur. Rachmaninoff a retravaillé cette pièce dans son opus 2 (Deux Pièces pour violoncelle et piano – 1892) et l’a également intitulé Prélude.

La pièce la plus conséquente est la Fugue en ré mineur, éditée

sans l’autorisation du compositeur en 1940 par Muzgiz, à Moscou.

La première chose qui m’interpella en la déchiffrant fut la

largeur incroyable des mains pour lesquelles ce morceau avait été

composé ; ce sont des mains d’adulte, et bel et bien celles d’un

adulte pianistiquement très averti, demandant une grande souplesse

digitale pour arriver à prendre les accords très larges sans être

tendu du bras ! Indépendamment du style du jeune artiste, déjà

bien différent de celui de son camarade de promotion Alexandre

Scriabine, qui, âgé d’environ un an de plus, composait également

ses premières pièces, et de la maturité de composition de l’œuvre,

sa qualité de mélodiste, qu’il gardera toute sa vie, est déjà

apparente. La pièce a été éditée sous l’Union Soviétique sous le

nom de Pièce en ré mineur. En fait, l’esquisse qui fut utilisée

pour cette édition n’était pas complète et contenait deux

suggestions de modifications, dont deux mesures qui ont été

barrées dans le manuscrit, à certains endroits tellement illisible

que l’éditeur a mentionné la possibilité d’inexactitudes dans la

retranscription imprimée, mais les trois feuillets qui la

composaient pouvaient se jouer sans que l'on s’aperçoive qu’il

manquait les deux feuillets intermédiaires du développement.

Ainsi, Sikorski édita en 1992 cette pièce telle quelle en y

rajoutant quelques nuances évidentes pour un pianiste

professionnel. Le manuscrit était non signé, sans titre, paraphé à

la dernière page et daté ‘fin ‘89’. Rachmaninoff avait

originalement noté le texte à quatre temps et ensuite corrigé la

mesure en valeurs ternaires.

Ce n’est qu’en 2007 que le mystère de cette Pièce en ré mineur fut

révélé dans son intégralité avec le projet d’édition complète des

œuvres du maître, y compris les esquisses inédites : Rachmaninoff

s’était amusé à essayer différentes signatures sur l’un des

feuillets manquants en y rajoutant les initiales S. R. et celles

de son père V. R. Un immense gribouillis bourré de fautes

d’écriture, de mesures barrées, de rajouts ou de superpositions de

mesures pouvant être jouées alternativement, demanda un soin

particulier pour la retranscription éditoriale. Mais les fautes

d’écriture subsistèrent. Cette pièce a une valeur historique dans

le sens où elle nous montre le cheminement intellectuel de

Rachmaninoff. Il avait l’habitude de très facilement se lasser

d’un morceau en le répétant à chaque concert et improvisait

librement autour du texte, si bien que certaines critiques

anglaises avaient écrit qu’il "ne savait pas jouer ses propres

œuvres " ! Il en était de même avec son procédé de création,

laissant des feuilles d’esquisses dont il exploitait le contenu

des années après, en modifiant ou révisant radicalement une pièce,

en insérant un passage esquissé et en composant autour (nous

connaissons à ce jour trois versions très différentes du Quatrième

Concerto). Ainsi, dans le feuillet manquant, on retrouve note pour

note et dans la même tonalité, un passage du Moment musical op. 16

n° 4 en mi mineur. La Fugue en ré mineur est une preuve que la

musique est une gigantesque matière organique et que chaque pièce

génère en elle une infinie série de possibilités d’exploitation du

même matériau de base.

Ainsi, Anton Arensky, le professeur de composition de

Rachmaninoff, s'inscrit dans la même démarche. Ayant donné à

l’origine le sujet de fugue comme travail scolaire à son élève, et

apparemment séduit par le sujet de son jeune élève, il le

réutilisa pour écrire sa propre une fugue, qui est jointe en

première audition à la fin de ce CD. Bien sûr, nous ne pouvons pas

parler de fautes d’écriture dans le présent cas avec un

compositeur aussi méticuleux et avisé qu’Arensky et la ‘fuguette’

fut éditée avec toutes les indications de dynamiques, conformément

au travail d’un compositeur abouti.

Les Quatre pièces pour piano ont été publiées illégalement chez Muzgiz en 1948. Bien que la date 1887 apparaisse au crayon, rajoutée par une main étrangère, et que l’éditeur note cette date comme la date originale de composition, les dernières recherches musicologiques montrent que la date de création serait plus vraisemblablement située autour des années 1891/92, après le cycle de Lieder de 1890/91, qu’il voulait nommer opus 1. Ces omissions volontaires montrent que Rachmaninoff refusa à plusieurs reprises l’édition de ses pièces avant la révision finale des manuscrits. L’opus 1 fut finalement accolé au Premier Concerto pour piano, seulement après la publication de son arrangement pour deux pianos. La troisième pièce, la Mélodie porte un titre qu’il attribuera plus tard à une pièce de son opus 3 (1892) ; elle sera d’ailleurs également révisée des années plus tard quand il aura émigré aux Etats-Unis. La dernière pièce est une gavotte à 5/4, rythme que Rachmaninoff n’utilisera qu’une deuxième fois dans sa vie avec son poème symphonique L'Île des morts op. 29. Là aussi, l’effet massif de l’écriture pianistique est dû à la forte utilisation des doublures et octaves aux deux mains.

Une réelle découverte dans mes recherches d’œuvres rares : les Quatre Improvisations (St-Pétersbourg, automne 1896, publiées par Taneïev et éditées par K. Kouznetzov en 1915-26 à Moscou) sont uniques dans leur genre. Il n’était pas rare à l’époque de voir différents compositeurs s’unir pour faire un ‘bœuf’ et composer une pièce à plusieurs. Ainsi naquit par exemple, deux générations auparavant, le fameux Hexaméron, une succession de variations sur un thème de l’opéra I Puritani de Bellini, composé par six compositeurs contemporains : Liszt, Thalberg, Pixis, Czerny, Herz et Chopin. Les professeurs de composition du jeune artiste, Anton Arensky, Serge Taneïev, Alexandre Glazounov se sont réunis autour de leur élève, vraisemblablement pour une farce musicale, et ont écrit une improvisation grotesque sur le papier. La chose amusante est que les compositeurs se succédant alternativement ont parfois continué une phrase musicale en plein milieu du discours du précédent. Sur la partition sont inscrits les noms de chaque artiste précisément à l’endroit même de son intervention.

Le Morceau de fantaisie date du 11 janvier 1899. La pièce de très

courte durée a été intitulée Delmo, mot dont l’origine reste

aujourd’hui encore inconnue.

La dernière œuvre de "jeunesse" de Rachmaninov présentée ici est

la Fuguette en fa majeur. Elle est datée à la fin du manuscrit "4

février 1899". Un an après, Rachmaninov, toujours dépressif,

allait bientôt composer son Deuxième Concerto pour piano qui lui

donnera l’ascension méritée.

Enguerrand-Friedrich Lühl-Dolgorukiy Bocholt, été 2009

Après avoir terminé brillamment ses études de piano à la Schola Cantorum, Enguerrand-Friedrich Lühl-Dolgorukiy complète sa formation en entrant à 15 ans au CNSM de Paris. 3 ans après, il obtient un Premier Prix de piano à l’unanimité. Parallèlement à son cursus de piano, il suit des cours d’analyse musicale, de jazz, de musique de chambre, de direction d’orchestre, d’harmonie et de contrepoint avec une passion grandissante. Après ses études, il entre dans le monde charismatique du Concours International et s’y consacre pleinement. Dès 1998, il devient lauréat de plusieurs concours, dont notamment Rome, Pontoise et le Tournoi International de musique. Depuis, il fréquente les grandes scènes d’Europe (récitals, musique de chambre, avec orchestre). La presse le qualifie unanimement de concertiste international. Il travaille depuis 2005 pour le compositeur américain John Williams, pour lequel il transcrit les partitions de ses plus grands thèmes de musique de films pour piano seul et deux pianos. Il a enregistré en 2003 le CD « John Williams au piano vol. I » avec ses propres arrangements des plus grands thèmes d’Hollywood pour piano seul. Son catalogue de compositeur est considérable : six ymphonies, deux concertos pour piano, de la musique de chambre, diverses pièces pour soliste et orchestre, environ 120 pièces pour piano seul, des orchestrations et réductions, une musique de film...

![]()

“From when can one call a work an opus #1 ?” This is a question

which as a composer I have been asked many times. It’s true that

the decision by an artist to create his own catalogue of works by

laying down the first stone is a mystery. In my opinion nothing

has been written about this very personal subject. Therefore from

and when and more importantly on what basis did I decide to call a

work ‘opus number one’, to commence a repertoire which will

increase constantly until the end of my life ?

Is it a first work, from the moment that you succeed in writing

some notes on a sheet of paper in a fairly coherent way, and to

which one never returns to, and the said sheet of paper then

gathers dust in the drawers of musicologists ?

Or is it the experience of youth which makes one believe that we

have acquired sufficient knowledge in the profession to have

written a piece of music which is playable for the rest of

posterity, even if it is unimaginable to envisage this vocation

with the professional conscience of an adult ? Or is it the desire

to do as the great musicians do, to finish things, the need to

feel mature and responsible in a certain manner ?

Certain composers revisit entirely their work before designating

it as an opus #1, which is deserving of this name ; others get

help so as to leave to prosperity a work of quality despite a lack

of experience in someone so young; others don’t allocate any

numbers to the works and leave a form of chaos consisting of

scattered pages devoid of dates and references. The method varies

according to the composer’s personality. Regarding myself I had

many opus #1s before deciding that the transcription of Gustav

Mahler’s First symphony for piano at age eleven was going to be

the starting point of the works that were to follow later. I

started like everybody else with two small pages of notes hardly

sketched out fully without any apparent link with other works and

then by a piece for piano some years later. Then another wave of

epiphanies occurred and opus #1 was delayed again. It wasn’t until

many years later, almost at the end of my music studies that my

catalog of works became definitive. I also put aside a number of

works and either destroyed or took back certain works; even though

when I was a small child I had sworn never to rework anything. But

music, like art and everything else is a movement and I have to

admit that the only thing which counts for a work of art is

quality which insures its life beyond future generations.

Regarding the romantic composers, most of them have a common

denominator. The opuses #1 are often large scale works : a Sonata

in four movements by Beethoven, a Concerto by Rachmaninoff and a

Symphony by Stravinsky ; as for myself it was this huge

transcription of Mahler’s First Symphony. I think this must have

been a need to prove something to oneself by starting with some

major work to be immersed in a sphere of art even if one has not

completely understood everything.

The evolution of the personal music style has no connection with

the quality of the piece due to the mastering of technical tools

for writing and one’s musical maturity. It is not about making a

tonal work from one’s youth into a serial work under the pretext

that one has evolves and that the original was badly composed

because it is tonal. As long as he respects the criteria of

harmony and counterpoint, the necessity of structure and

architecture, the piece remains nevertheless one of quality even

if the language is different.

This is why for example Webern maintained as his opus 1 the

enormous Passacaille for orchestra which is essentially tonal and

written in a language much different from his opus 2, which he

wrote a few months later. The modifications that one may make

later, are first of all technical, and then esthetic. The quality

should not interfere with one’s personal taste, or else only in

particular circumstances. And one learns about oneself by “finding

the voice which is our essence” (which is what Henry Sauguet told

me when I was very young during our one and only discussion). And

so, in this CD, Rachmaninoff had composed his opus 1 well before

the official version of the official opus 1, the Concerto for

piano from 1891 (which wasn’t definitive until 1917 after a lot of

revisions).

The Four Pieces for piano from the first opus are dated 1887,

whereas Rachmaninoff had already composed a certain number of

other pieces which were elaborate, which is to say that they were

exercises in style for his studies. The scores edited without

authorization by the composer or his heirs from the time of the

Soviet Union were printed without any corrections and totally

devoid of any variations in dynamics, or further instructions. The

first official edition of certain pieces published by Sirkoski did

not help tremendously because it only cleaned up some difficult

lines, hard to decrypt, and added some instructions and

indications of nuances according to what the text suggested.

I had to begin a interesting work of reconstruction of the score

only using my musical skills to give it shape and temporary

assembled every piece from what I knew of Rachmaninoff’s style as

a pianist – I collect old recordings by composers playing their

works and was lucky to own the complete collection of recordings

by the master, which I used as a reference –, what I knew about

his personality after studying his biography for a long time, by

searching through different archives to find unusual moments from

his life and his work, without forgetting my principal quality as

a composer, which is very close to Rachmaninoff’s style of

composing. I had to correct some editorial typing errors or lapses

by the composer (we all do it!). All this allowed me to construct

a coherent interpretation and above all plausible.

Curiously, the young Rachmaninoff expressed himself very often in

his work in d minor : it is true that we already find this

recurring tonality on this recording, especially both in the suite

and in the fugue. Maybe it was pure coincidence if one did not

take into account the orchestral pieces, which is to say at the

beginning, the suite was written for orchestra, and his symphonic

poems (Youth Symphony, the Prince Rostislav), as well as his

Scherzo are all in the same tonality.

The Three Nocturnes are the very first pieces of Rachmaninoff

known and published illegally by Muzgiz in 1949 ; they are dated

“n° 1 November 14th-22d 1887”, n° 2 “November 22d-25th 1887” and

n° 3 “December 3d/ January 12th 1888”. Devoid of any nuances these

pieces have nothing in common with the dreamy atmosphere of the

Chopin Nocturnes.

In fact, I find it difficult to imagine the reason why

Rachmaninoff called these pieces so, because most of this music

has no nocturnal touch at all. Quite the opposite is true. The

last page of the third nocturne was lost and the six bars of the

end were copied by the editor from the beginning of the piece,

because it was impossible to finish on the last fermata.

The Suite in d minor is a master piece of this period which

survived. The manuscript of a piece for piano without an opus

designation was for a long time kept confidentially in the

archives of the Glinka museum up until 1964 ; then the work was

transferred to the archives of Rachmaninoff’s cousin Alexander

Siloti. The absence of a front page indicating the title and the

name of the composer as well as the signature made the

musicologist’s task of attributing a composer to the work

difficult. The period of composing was consequently established

around his years of study at the conservatory. In a letter dated

January 6th 1891, Rachmaninoff told N. Skalon : “For two and a

half days now I have not stopped writing. I have just finished the

orchestration of my suite. Everything is well, except after

playing it on the piano, my right hand felt sore…” In his next

letter, the day after, he wrote : “Regarding my suite for

orchestra I didn’t have any success. They are not going to play

it, because it is written for a symphony orchestra which features

instruments which we don’t have here at the conservatory. So I’m

going to have to wait until next year when I will find an

opportunity to organize a concert of my own and I will perform it.

I gave it to Tchaikovsky to have a look at and I trust him

implicitly about everything.” The story of the suite remains

unclear. However, one thing is certain : the first opening bars

remind one strangely of the beginning of the Prelude op. 3 n° 2

and especially the beginning of the Second Concerto.

Canon (first illegal publication par Muzyka 1983). Studies place

this manuscript between 1889 and 1892. Rachmaninoff had a period

of intense contrapuntal work during his apprenticeship years,

during which he did not hesitate to put into practice the

competence learnt in Arensky’s and Taneiev’s classes.

The Prélude in F Major (20.7.1891) is the only piece to have been revised by the author. Rachmaninoff reworked this piece in his opus 2 (Two Pieces for cello and piano – 1892) and he also called it Prelude.

The first great piece of importance is the Fugue in d minor,

edited without the composer’s authorization in 1940 by Muzgiz in

Moscow. The first thing that struck me during my decrypting was

the size of the hands necessary to play this piece; although only

very young at the time, Rachmaninoff had already the hands of an

adult, technically very far advanced which demanded great finger

skills in order to play the notes without being stretched to the

limit. Independently of the young artist’s style, already very

different from that of his class mate Alexander Scriabin, who

about a year older, Rachmaninoff was already composing his first

pieces, and from the maturity of the composition and its melodic

quality, something he would keep for the rest of his life, was

already apparent. The piece was edited under the Soviet Union and

entitled piece in d minor. The sketch which was used for this

edition was incomplete and contained two suggestions for changes

of which two bars were crossed out in the manuscript. The

manuscript was so unreadable in certain places that the editor

felt obliged to mention the possibility of confusion in the

printed version. But the three pages making up the manuscript

could be played without one noticing that there were two pages

missing from the manuscript. So Sikorski printed in 1992 this

piece as it was and added some interpretation comments which are

obvious to professional players. The manuscript is an unsigned

pencil draft, dated at the end « fin ‘89 » (in French meaning “end

of...”). Rachmaninoff originally wrote the music in 4/4 time,

later changing this to 12/8 time.

It was only in 2007 that the mystery of this Piece in d minor was

revealed in its totality with the complete works edition project,

including the unpublished sketches : Rachmaninoff amused himself

by trying out different signatures on the missing pages by adding

the initials S.R. and those of his father V.R. – creating immense

chaos full of composing mistakes, crossed out bars of music,

add-ons and overlapping bars which could be played alternatively.

This demanded particular care for the editorial retranscription.

But still mistakes survived. This piece has a historical value in

the sense that it shows us Rachmaninoff’s intellectual progress.

He tired easily of one piece by playing it repeatedly on stage and

so improvised freely around the text in a way that certain English

critics thought he didn’t know how to play his own works! It was

the same for his creative process, leaving sheets of sketches that

he had used sometimes in the years after or modifying or revising

them radically, either inserting a passage in a piece and

composing around it (to date, we know three very different

versions of the Fourth piano concerto). And so, in the missing

page, we find note for note, even in the same tone, a passage from

the Moment musical op. 16 #4 in e minor. The fugue in d minor is

proof music is a gigantic organic concept and that every piece

generated in it is an infinite series of possible combinations.

Anton Arensky, Rachmaninoff’s teacher, seems to have thought the

same thing, because originally he had given the theme to

Rachmaninoff as homework and then, apparently seduced by the young

student’s work, he used the same musical theme to compose a fugue

of his own which is added to the first performance at the end of

this CD. Of course, we cannot speak of writing errors in the case

of such a meticulous composer as Arensky and the little fugue was

edited with all the instructions for interpretation.

The Four Pieces for piano were published illegally by Muzgig in

1948. Although the year 1887 appears pencilled in in a foreign

hand amending Rachmaninoff’s autographed title page for each

manuscript, recent research now dates these copies from 1891/92,

after the 1890/91 collection of songs Rachmaninoff initially

intended as his op. 1. These types of omissions suggest

Rachmaninoff decided against publication of these pieces before

the final proofreading of the manuscripts. Opus 1 was reassigned

to the First Piano Concerto only after the publication of the

two-piano arrangement in 1894.

The third piece, the Melody has a title Rachmaninoff gave it later

as part of his opus 3 (1892) which would be revised years later

when he emigrated to the United States.

The second piece is a Gavotte with Rachmaninoff only uses a second

time in his life, in his symphonic poem The Isle of the Dead op.

29. There also, the effect of the piano writing is due to the

strong use of doubles and octaves for both hands.

A real discovery during my search for rare works by Rachmaninoff : the Four Improvisations ‘St Petersburg, autumn 1896 published by Taneiev and edited by K. Kuznetzov in 1915-26 in Moscow) are unique. It wasn’t unusual at that period to see several composers getting together for fun to compose a piece of music. Two generations previously, the famous Hexameron, a succession of variations on a theme from the opera I Puritani by Bellini, was composed by six contemporary composers : Liszt, Thalberg, Pixis, Czerny, Herz and Chopin. Rachmaninoff’s teachers, Anton Arensky, Serge Taneiev and Alexander Glazunov came together with their student, probably to create a musical farce, eventually writing a grotesque improvisation. The amusing point is that the composers alternated with each other and composed a musical phrase while still conversing. On the score are written the names of all the artists at exactly the spot where they composed their contribution.

The Fantasy Piece dates from January 11th 1899. The very short piece is entitled Delmo, whose meaning today still remains a mystery.

The last youthful work by Rachmaninoff is a Fuguette in F Major. It is dated February 4th 1899. A year later, Rachmaninoff, still suffering from depression, composed his Second Piano Concerto which assured him posterity.

Enguerrand-Friedrich Lühl-Dolgorukiy, Bocholt, 2009

translation : Patricia Nolan

Enguerrand-Friedrich Lühl-Dolgorukiy was born in Paris in 1975. He started his studies as a pianist at the Schola Cantorum then completed his training by entering the CNSM of Paris aged 15. Three years later he obtained first Prize for piano. Parallel to his piano cursus he studied music analysis, chamber music, orchestral conducting, harmony and contrapoint. Since 1998 he has won several international competitions and plays at prestigious venues throughout Europe. The press is unanimous in considering him as an international concert pianist. His 1300 pages of musical arrangements will be edited at a future date. His composer’s catalogue is impressive : six Symphonies, two piano concertos, chamber music, various pieces for soloist and orchestra, around 120 original pieces for piano, orchestrations and arrangements, film music…

![]()

![]()

Accueil | Catalogue

| Interprètes | Instruments

| Compositeurs | CDpac

| Stages | Contact

| Liens

• www.polymnie.net

Site officiel du Label Polymnie • © CDpac • Tous droits

réservés •