|

|||||

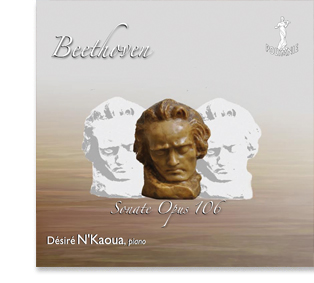

Beethoven,

Sonate Op. 106

Désiré

N'Kaoua, piano

POL 209 146

Ludwig van Beethoven

Sonate n°29 Hammerklavier Op.106

Allegro

Scherzo, assai vivace

Adagio sostenuto. Appassionato e con molto sentimento

Largo - Allegro risoluto

Beethoven

Sonate n°29 Hammerklavier Op.106

Pendant l’été 1818, en composant sa gigantesque

sonate opus 106 pour piano, Beethoven était parfaitement conscient

de confronter ses futurs interprètes à une exigence technique et

de signification musicale encore jamais atteinte dans les

vingt-huit sonates précédemment écrites pour le piano. Il pensait

même qu’aucun interprète aussi doué fut-il n’oserait approcher

cette œuvre avant cinquante ans ; et, en fait, au cours des neuf

années qui lui restaient à vivre, il n’a pu ni jouer cette œuvre

en public (ses moyens pianistiques ayant diminué), ni l’entendre

jouée par d’autres interprètes. Une légende raconte que trois

concertistes célèbres en Europe se désistèrent un mois avant leur

présentation, se sentant dans l’impossibilité de surmonter cette

sonate inscrite dans leur programme depuis longtemps. Fort

heureusement, le délai de cinquante années prévu par Beethoven

pour la diffusion de son œuvre fut raccourci grâce aux deux

remarquables interprètes qu’étaient Franz Liszt, admirateur

inconditionnel de Beethoven depuis son enfance hongroise, et Clara

Schumann, virtuose qu’aucune difficulté ne rebutait.

Il était émerveillé par la toute récente invention du "Hammer

Klavier", piano à marteaux dont un exemplaire venait de lui être

offert par la fabrique Broadwood de Londres. Et c’est sans doute

la découverte de cet instrument (qu’il considérait comme le piano

de l’avenir) qui déclencha le projet d’écrire cette sonate de

quarante-sept pages dont le quatrième mouvement n’est autre qu’une

fugue monumentale.

Il semble que les séjours plus ou moins longs à

la campagne, tant appréciés par Beethoven, aient donné naissance à

ses plus riches inspirations. "J’aime mieux les arbres que les

hommes", était sa devise préférée et il définissait ses promenades

comme "une visite à ses amis les arbres". Il détestait les grandes

agglomérations et plus particulièrement Vienne dont il jugeait le

public frelaté, inculte, partial et superficiel. Il affirmait

comme le fera Prokofieff au siècle suivant : "J’écris pour

l’avenir ".

Cette période de l’été 1818, vécue comme une triste retraite dans

le village de Mödling situé à une vingtaine de kilomètres au sud

de Vienne dans la seule compagnie de son neveu Karl, nous laisse

apparaître un Beethoven malade, dramatiquement démuni

financièrement, abandonné de ses mécènes disparus ou partis à

l’étranger. Il hésitait même à sortir de sa petite auberge et

allait jusqu’à écrire à son élève F. Ries qui demeurait à Londres

: "Si vous saviez comme il est dur d’écrire pour gagner son

pain...". Et c’est pourtant dans de telles conditions de misère

absolue que Beethoven écrivit la monstrueuse Sonate Opus 106 et

deux autres chefs d’œuvres : la 9ème Symphonie et la Missa

Solemnis.

Concernant la Sonate Opus 106, il faut noter qu’elle est la seule

sonate (et peut-être la seule œuvre ?) dont chaque mouvement est

précédé d’une indication métronomique de la plume de Beethoven :

les œuvres précédentes, et même suivantes, comportent seulement

des indications de caractère (allegro con brio, andante sostenuto,

etc...) offrant aux interprètes un choix plus large. Sans doute la

volonté de fixer un tempo précis n’est-elle pas étrangère à

l’invention du métronome deux ans plus tôt par J. N. Mälzel ;

malheureusement l’indication 138 à la blanche donnée par Beethoven

rend le premier mouvement illisible sous les doigts des

interprètes les plus chevronnés qui souhaitent la respecter. Le

pianiste Paul Loyonnet, dans son merveilleux ouvrage sur les 32

Sonates de Beethoven, la déclare simplement "injouable" à ce

tempo. D’autre part, la première publication à Londres du vivant

de Beethoven indique le même nombre (138) mais cette fois à la

noire, ce qui n’est pas crédible non plus pour le motif inverse.

Je pense que la réalité se situe entre les deux indications et ce

qui en ressort est le désir de Beethoven d’en faire ressentir la

pulsation à deux temps plutôt qu’à quatre.

L’allegro initial reflète parfaitement

l’ambivalence du caractère beethovenien que tous ses biographes de

l’époque dépeignent comme capable de passer en quelques secondes

d’une terrifiante violence à l’irrésistible tendresse (son visage

se couvrait de larmes à la découverte d’un cadavre de chien

abandonné sur un trottoir) ; en lui cohabitaient et alternaient

révolte permanente et douce résignation. Geste significatif, s’il

en fut : Beethoven mourut en tendant vers le ciel son poing fermé.

Le second mouvement est un scherzo rapide, vivant et sarcastique

mais qui cède en son milieu la parole à une rêverie toute

schubertienne.

L’adagio, sans doute l’un des plus inspirés que Beethoven ait

jamais écrit, est un moment sublime de grande sérénité. Il n’est

pas sans évoquer, dans sa variation en triples croches cet autre

chef d’œuvre qu’est la partie lente du Concerto en sol de

Ravel.

Enfin, une courte page d’introduction lente composée de

fragments très courts qui se superposent sans s’enchaîner, comme

une idée qui se cherche, nous conduit victorieusement au thème

(mesure 17) d’une magistrale fugue de 384 mesures qui tend le plus

grand nombre

de pièges à ses exécutants. Peut-être s’agit-il du dernier défi

que s’est imposé Beethoven ?

En effet, les mélomanes viennois aux

idées souvent très arrêtées n’attribuaient l’appellation de

"compositeur" qu’à ceux qu’ils savaient capables d’écrire

correctement une fugue. Et Beethoven qui souhaitait donner de lui

une apparence d’indifférence aux méchantes appréciations était en

réalité très vulnérable. Nous noterons qu’aucune fugue n’apparaît

à l’intérieur d’une sonate avant la 28ème opus 101 et que,

exception faite de quelques pages de musique de chambre, cette

expérience ne se retrouvera que dans la sonate n°31 Opus 110.

![]()

Jean-Claude Soldano

Compositeur, arrangeur et éditeur Sacem, peintre (membre de

l'association Bassompierre des Peintres du Spectacle),

Jean-Claude Soldano est actuellement professeur titulaire de

Piano-Jazz, de Synthétiseur et de M.A.O (Musique Assistée par

Ordinateur) au Conservatoire d'Ozoir-la-Ferrière.

Après des études musicales au Conservatoire de

Fontenay-sous-Bois (Classe d'écriture de Solange Chiapparin du

CNSM), à l'Ecole Normale de Musique de Paris (Classe de piano de

Dusan Tadic ancien élève d'Alfred Cortot) et à l'Université de

Paris-Sorbonne (licence de musicologie), Jean-Claude Soldano se

perfectionne auprès du pianiste Harry Gatibelza (harmonie du

jazz, improvisation) et de la Bill Evans Piano Academy

(Directeur : Bernard Maury).

Il accompagne au piano, pendant de nombreuses années, le groupe

vocal de gospel "Accord Singers" (Festival de Jazz d'Argelès,

Festival du Marais à Paris, Festival des Caraïbes...).

En 2006,

il crée la maison d’édition qui porte son nom.

Ses pièces sont

régulièrement choisies dans des concours nationaux et

internationaux (Confédération Musicale de France, Grand Concours

International de Piano Svetlana Eganian, Concours des Clés d’Or,

Concours Steinway-Le Parnasse, Concours Musical de France,

Fédération Française de l’Enseignement Musical...).

Jean-Claude Soldano a remporté le Prix International

d’Excellence en Composition Musicale 2011 (National Academy of

Music / State of Colorado / U.S.A) avec ses pièces pour piano

Sicilienne et Derrière la colline.

Cette dernière pièce lui a

permis, en 2012, d’obtenir un Prix d’Honneur auprès de la

Fondation Ibla (New-York) sous le haut patronage de l’Unesco.

![]()

Beethoven

Sonate n°29 Hammerklavier Op.106

During the summer of 1818,

as he was composing his gigantic Hammerklavier Sonata Op 106,

Ludwig van Beethoven was fully aware that he would be

challenging pianists with a far more demanding piece than the 28

previous sonatas that he had written for piano.

He even believed

that no performer, no matter how gifted, would dare to even come

close to playing the sonata for another 50 years. In fact,

during the nine remaining years of his life, he, himself, was

never able to play the Opus 106 in public (by that time he had

lost most of his ability to play). And he never heard it played

by other performers.

Legend has it that three famous European pianists cancelled

their shows a month before the concert dates for they felt

incapable of mastering the sonata, even though it had been in

their program for a long time.

Thankfully, the 50-year delay

predicted by Beethoven was shortened by two remarkable

performers: the Hungarian-born Franz Liszt, who was a huge fan

of Ludwig, and Clara Schumann, who was such a virtuoso that

nothing would scare her off.

At the time, Beethoven was amazed by the recently invented

hammer keyboard—he had just been offered one by the London-based

piano maker Broadwood. The discovery of this instrument (which

he considered to be the piano of the future) probably sparked

the writing of this 47-page sonata. Its fourth movement is no

less than a colossal fugue.

It seems that Beethoven’s time in the countryside, which he was

so fond of, gave rise to his most inspiring music. “I prefer

trees to men” was his favorite saying, and he would call his

walks his “visits to his friends, the trees”. He hated big

cities and most particularly Vienna. He deemed Viennese

audiences fake, uncultured, biased and superficial. He would

say, as Prokofieff did a century later: “I write for the

future”.

During the summer of 1818, he sadly retreated to the village of

Modling, 20 or so kilometers south of Vienna. His only companion

was his nephew Karl. He was ill, in dire straits financially and

abandoned by his patrons who had vanished or gone abroad. The

composer even hesitated to leave his small hostel and once wrote

to his student, Ferdinand Ries, in London “If only you knew how

hard it is to earn one’s bread”. Yet, despite such misery,

Beethoven composed his monumental Sonata Opus 106 and two other

masterpieces: the 9th Symphony and the Missa Solemnis.

The Sonata Opus 106 remains the only sonata (and perhaps the

only piece composed by Beethoven) which contains, before each

movement, metronomic notes from Beethoven himself: previous and

following pieces only include instructions such as allegro con

brio, andante sostenuto, etc... thus offering performers wider

choices.

There is no doubt that the will to impose a specific tempo has

to do with the invention of the metronome two years earlier by

J.N. Mäzel. Unfortunately, the instruction “half-note 138 BPM”

given by Beethoven makes the first movement seemingly impossible

even for the most experienced performers.

In his wonderful book about the 32 Beethoven sonatas, the

pianist Paul Loyonnet, simply declares it “unplayable” at this

tempo. On the other hand, the first edition, published in London

during Beethoven’s lifetime, indicates “quarter-note 138 BPM”,

which is no more credible for the opposite reason. I think the

truth probably lies in between the two instructions. It reflects

Beethoven’s desire to have a beat of two rather than four.

The initial allegro shows the fluctuation in Beethoven’s moods,

which biographers described as ranging from terrifyingly violent

to irresistibly tender within seconds (he could burst into tears

when coming across the dead body of a stray dog on the

sidewalk). He alternated between angry revolt and quiet

resignation. His last gesture gives us insight into his turmoil:

Beethoven died clenching his fist towards the sky.

The second movement is a Scherzo. It is fast, vivid and

sarcastic but midway it transforms into a Schubert-like reverie.

The adagio, probably the most inspired that Beethoven ever

wrote, is a sublime moment of great serenity. In its variation

in eighth note triplets, it recalls another masterpiece: the

slow movement of the Concerto in G by Ravel.

Then, there is this short and slow introduction page, made of

very short fragments which seem to be superimposed without

order. Like a wandering idea, it leads us to the theme, (at

measure 17), a magistral fugue made of 384 measures that any

performer would consider incredibly tricky.

Perhaps it is the last

challenge that Beethoven imposed upon himself. Viennese music

lovers, who had a very narrow definition of composers, only

considered those who could correctly compose a fugue worthy of

that name. Beethoven who wanted to appear indifferent to harsh

critics was, in fact, vulnerable. No fugue appears in his

sonatas before the sonata number 28 opus 101 and, other than a

few pages of chamber music, can only be found again in the

Sonata number 31 Opus 110.

Désiré N’Kaoua

Translated by

Laurance N'Kaoua

![]()

Dés son plus

jeune âge, Désiré N’Kaoua, pianiste français né à Constantine il

y a 86 ans, manifeste des dons exceptionnels qui lui permettront

d’être à 18 ans, 1er Prix du CNSM de Paris, de se perfectionner

avec Marguerite Long et Lazare Lévy.

A 27 ans, il obtient le

titre envié de 1er Grand Prix du Concours International de

Genève. Dès lors, il effectue de nombreuses tournées en Europe,

en Asie, aux USA et le succès que remportent ses concerts fait

de lui le soliste invité des plus grands orchestres : Berlin,

Varsovie, Prague, Budapest, Bucarest, de Radio-France, de la

R.A.I..

Parallèlement à sa carrière de soliste international, Désiré

N’Kaoua, dont la valeur pédagogique a dépassé le cadre de nos

frontières, fut professeur au Conservatoire Supérieur de Genève,

de Versailles tout comme à l’Ecole Normale de Musique de Paris

et à la Schola Cantorum. Il a aussi donné de nombreuses

master-classes tant en France qu’à l’étranger.

Fondateur en 1986 du Concours International de Sonates de

Vierzon, il participe aussi à la création de l’Académie

Internationale de Musique des Pays de la Loire ainsi que du

Festival Estival de Guerande, .

En 1988, Marcel Landowski, le décore des insignes de Chevalier

dans l’Ordre National du Mérite au titre d’Ambassadeur de la

Musique Franca̧ ise à l'étranger.

Il donne un concert au Vatican

en 1988 pour commémorer la mort de F. Chopin. Sa passion de la

musique trouve aussi sa réalisation dans de nombreux

enregistrements (Mozart, Schubert, Chopin, Debussy, les

Intégrales de Chabrier, Ravel, Alain, Roussel, etc...).

En 1997, Désiré N'Kaoua a été promu, sur proposition du Premier

Ministre, Officier dans l’Ordre National du Mérite toujours au

titre d’Ambassadeur de la Musique Franca̧ ise à l'étranger. Il a

donner plus de 2000 concerts.

![]()

From the time

of his earliest childhood, Désiré N'Kaoua, a French pianist born

in Constantine, Algeria, was gifted with outstanding musical

talents. His musical gifts allowed the virtuoso to win the First

Prize of the Paris National Superior Music Conservatoire at age

18. At this age, N'Kaoua became a soloist with the Berlin

Philharmonic Orchestra. At age 27, the piano virtuoso was

awarded the much-praised and rarely-awarded First Grand Prize of

the Geneva International Competition. N'Kaoua also won the Gold

Medal at the Vercelli International Competition and the First

Prize at the Competition Alfredo Casella of Sienna. He later

came the "Honor" Soloist of Italy's Sienna Academy.

Désiré N'Kaoua toured both Werstern and

Eastern Europe. The outstanding successes of his piano

performances made him a soloist with the most prestigious

orchestras : the Philharmonic Orchestras of Berlin, Warsaw,

Prague, Budapest, Athens and Roman Switzerland accompanied him.

N'Kaoua was also a soloist with the Chamber Orchestra of Berlin,

The Radio-France Philharmonic Orchestra, the Lausanne Chamber

Orchestra and many others.

In 1988, the French musician received

France's National award of Chevalier in Ordre du Mérite, from

the hands of French composer and music official Marcel

Landowski. The award officially nominated N'Kaoua the ambassador

of French music abroad. In 1989, he gave his thousandth recital.

In addition of his career as a soloist,

N'Kaoua, whose reputation as a piano professor has long gone

beyond France's borders, also gives master classes in France and

abroad.

The artist has

also expressed his passion for music via many compact disks

(N'Kaoua has recorded works by Chopin, Schubert, Mozart,

Chabrier, Jehan Alain, Roussel etc. )

![]()

Désiré N’Kaoua

is a French pianist; he borned in Algeria 86 years ago.

From the time of his earliest childhood, Désiré N’Kaoua proved

to have exceptional musical gifts. At age 18, the French pianist

received the First Prize of the National Superior Music

Conservatory of Paris, where he attended classes with such

masters as Lazare Lévy and Lucette Descaves.

At 18, N’Kaoua

first performed as a soloist with the Berlin Philharmonic

Orchestra, and throughout his career he has appeared with the

most prestigious musical ensembles, including the Philharmonic

Orchestras of Berlin, Warsaw, Prague, Budapest, Athens and Roman

Switzerland, the Radio-France Philharmonic Orchestra, the

National Philharmonic Orchestra of Bucharest and the Lausanne

Chamber Orchestra, to name only a few.

At 27, the virtuoso was

awarded the much praised yet rarely discerned First Grand Prize

of Geneva’s famous international competition. Other prizes

include the Gold Medal at the Vercelli international competition

in Sienna and the First Prize at the Alfredo Casella competition

(Italia).

The artist has also made numerous recordings in France

and abroad, including works by Chopin, Schubert, Mozart,

Chabrier, Jehan Alain, Fauré, Debussy and Ravel. .

In addition

to a fulfilling career as a soloist, N’Kaoua is a respected

pedagogue, with a reputation depassing France’s borders. He has

taught at the Superior Music Conservatory of Geneva and at the

National Conservatory of Versailles, France. Désiré N’Kaoua is

currently teaching at both the Ecole Normale de Musique de Paris

and the Schola Cantorum, two of France’s most prestigious piano

schools.

In France, he has created the International Music

Academy of the Pays de la Loire, a summer music school. He is

also at the origin of several competitions: he founded the

Sonata Competition of Vierzon in 1986, Guerande’s Festival

Estival in 1989 and the International Competition of French

Music in 1991.

The Prime Minister of France recently promoted

Désiré N’Kaoua to the rank of Officer in Ordre National du

Mérite, renewing his mandate as “Ambassador of French Music”.

![]()

Accueil | Catalogue

| Interprètes | Instruments

| Compositeurs | CDpac

| Stages | Contact

| Liens

• www.polymnie.net

Site officiel du Label Polymnie • © CDpac • Tous droits

réservés •